Introduction to the Study

Art historians have long been aware of the artistic relationship between Camille Pissarro and his sons Lucien and Georges, due in large part to the extensive letters he wrote. However, it wasn't until 2013 that the first technical study comparing Camille and Lucien’s materials and techniques was carried out at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Since then, there have been new developments and wider applications of noninvasive analytical techniques for the analysis of paintings. This current study expands on findings from the Courtauld’s technical study, connecting Camille and his first son Lucien to the typical painting practice of the 19th century.

The earlier study found that father and son used similar materials, but those materials did not dictate their techniques, which were stylistically different. They concluded that Camille’s painting was “direct and innovative” while Lucien’s was “limited but accomplished.” The authors adopted the assumption that Camille played the role of instructor to his son.

This study seeks to build on this initial understanding of the Pissarro family’s working relationship. Importantly, it also includes Camille’s second son Georges—an artist who has been little studied and remains relatively unknown to this day. Georges was, it would seem, a less enthusiastic student, not producing the output of work to his father’s standards. From primary source documents, it would seem that he received little advice from his father on painting techniques and materials. Instead, Camille urged his son to simply produce artwork. Although frustrated with him, Camille attempted to progress Georges’s artistic career by connecting him with dealers and sending him art supplies. Up until Camille’s death, he sent Georges money along with almost every letter, often complaining about how difficult it was to sell his own paintings to earn a profit. This essay looks further into topics touched upon in the Courtauld study, focusing specifically on the concepts of mattness, the sharing of materials, and the use of underpaintings in the Indianapolis artworks.

There are seven paintings by three members of the Pissarro family in the collection of the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA) at Newfields: four paintings by Camille Pissarro, two by his eldest son Lucien, and one by Georges, his third child. The four paintings by Camille—

Landscape (about 1864),

The Banks of the Oise at Pontoise (1873),

House of the Deaf Woman and Belfry at Éragny (1886), and

Woman Washing Her Feet in a Brook (1894)—were painted over a 30-year period, each about a decade apart, and thus represent the evolution of Camille’s style from Barbizon influence, through Impressionism, and into Post-Impressionism. Lucien’s

Interior of the Studio (1887) was painted just a year after Camille’s

House of the Deaf Woman, and both were painted during the brief period in which father and son experimented with pointillism. Georges painted

Rue de l’Épicerie (1898) four years after

Woman Washing Her Feet in a Brook. Ten years after Camille’s death, Lucien painted

Rye from Cadborough (1913) while in England.

Like Father, Like Sons

The Pissarros were a close-knit family, and this intimacy was reflected in their artistic output.

Camille often made paintings and sketches of his seven children. Other artists in Camille’s circle depicted the family too. For example, a lithograph by family friend Maximilien Luce titled

The Pissarro Family (1895) shows Camille and his children in Éragny engaged in various activities (his son Felix is depicted cutting a block print).

Despite his wife’s wishes that her sons embark on practical careers, Camille encouraged all five of his sons to become artists. Even though Lucien moved to England in 1890, the family spent much of their time together in Éragny-sur-Epte.

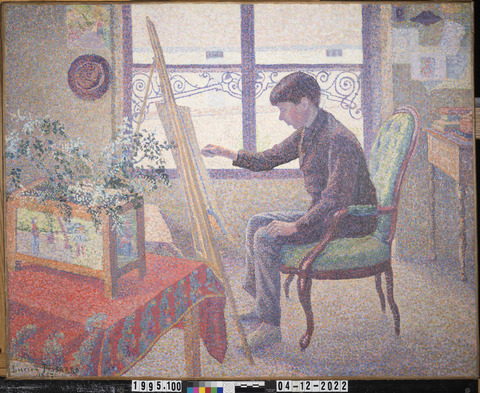

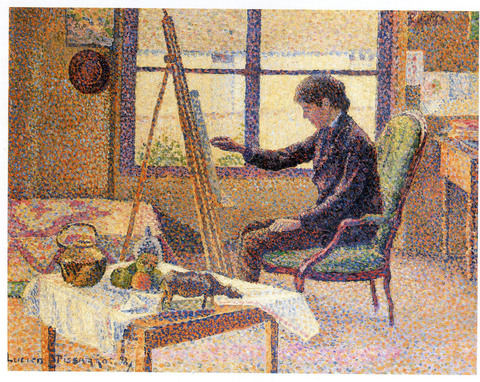

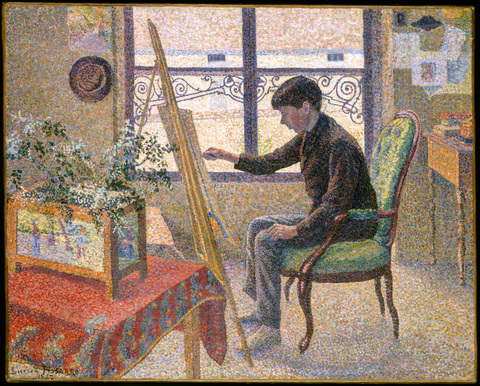

Interior of the Studio was painted by Lucien in his father’s studio in Éragny, depicting his brother Georges at the easel (fig. 1). Camille compiled albums of his children’s artwork, which they sometimes collaborated on.

Le Guignol (1889) is one of these manuscripts of miscellany that includes stories and poems illustrated with drawings and etchings by Camille and all five of his sons.

Figure 1: Front, visible light. Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Interior of the Studio, 1887, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift in memory of Robert S. Ashby by his family and friends, 1995.100.

Figure 1: Front, visible light. Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Interior of the Studio, 1887, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift in memory of Robert S. Ashby by his family and friends, 1995.100.

Camille was especially close with Lucien, his eldest son, and they started a regular correspondence in 1890 when Lucien moved to England. Camille recounted the goings-on in the Paris art world and at home. At times he took on the role of mentor, lecturing Lucien on how to express his own individual style. On 4 March, 1894 Camille wrote to Lucien:

I saw your two canvases at Contet’s; they are very pretty. At first sight I feel that you are still too close to my work; you should try a different execution and be attentive to the general values. In general, your colorations lack something; from the way objects are delimited one would say you practice tone division while first letting your color dry, you are afraid to mix. If I were you I would mix freely, I would not leave so many orange-colored commas. One feels that you are inhibited, but where there is inhibition there is no pleasure.

Sometimes Camille could not help but express his own taste to Lucien in hopes he would follow suit. Camille wrote Lucien on 26 November 1896:

If you remain in England, you will be associated rightly or wrongly, with English art… you must side with the art that best suits your temperament. It seems to me that your place is here [in France].

And again two days later:

Every time I noticed some defect in your work, I spoke of it to you, and I shall do so again… I urge you to devote yourself resolutely to your art, meaning the art of the impressionists… I fear only that you are yielding not to religious or mystical art, but to sentimental art. As I see it, mistakenly perhaps, the Pre-Raphaelites were somewhat sentimental and their descendants are much more so… Sensation, yes, sentiment, too, damn it!

However, Camille and Lucien’s relationship was not simply one of instructor and pupil. Lucien introduced Camille to ideas of pointillism through his friends Signac and Seurat in 1885.

Camille adopted this new “scientific” method of painting and forged a relationship with the two artists. He often shared with them which pigments he preferred. As a result, Seurat used zinc yellow in the reworking of his famous

Grande Jatte.

Lucien collaborated on a book of prints with his father in 1895 that illustrated the myths of Daphnis and Chloe — something Lucien proposed when he was beginning his career as a printmaker. He had founded the Éragny Press just a year earlier.

Camille would make the original illustrations complete with color notations and send them to Lucien, who would then cut the woodblocks.

It would seem that Camille’s relationship with Georges was more strained. In letters to Lucien, he appears frustrated with Georges and worries about his future career as an artist, finding him “changeable” and “easily discouraged."

On 18 February 1894, when Georges was 23 years old, Camille wrote to Lucien:

Georges and Titi [his brother Felix] went to Gisors for a walk; hardly any work has been done for several days; they seem to feel the need to do things at random, to walk, to play, to disguise themselves. I suppose youth is claiming its rights. I still do not know what Georges will decide to do…I should like to see Georges make up his mind to work modestly without taking himself too seriously, and arrange his life simply with what I can give him, while keeping himself in readiness for any opportunity to show his works; to do, in a word, what we old-timers have patiently done for years. One strives in vain…Long hair, dandyism, noise, count for nothing; work, observation and sensation are the only real forces.

Lucien had earlier depicted Georges at sixteen years old with his “long hair” in

Coin d’Atelier (fig. 2) from 1887. Perhaps Lucien was sensitive to Camille’s disapproval of Georges’s long hair. This may be the reason Lucien depicted Georges with short hair in the IMA’s version of the same scene (fig. 1),

Interior of the Studio, painted in the same year as

Coin d’Atelier. From the 1894 letter, it would seem that—much to his father’s chagrin—Georges still kept his hair long seven years after

Interior of the Studio was painted.

Figure 2: Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Corner of the Studio (Coin d’atelier), 1887, oil on canvas, Private collection. Photo by Peter Jacobs Fine Art Imaging.

Figure 2: Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Corner of the Studio (Coin d’atelier), 1887, oil on canvas, Private collection. Photo by Peter Jacobs Fine Art Imaging.

Unlike the exchange of ideas seen in letters between Lucien and his father, Camille gave Georges some constructive criticism on his artwork, but mostly he offered constant pleas to simply produce something. While at first Georges made artwork in a similar impressionistic style to that of his father, later in his career, Georges turned to a more decorative painting style, drawing inspiration from Orientalism. In his early career, he mainly produced watercolors and prints. His watercolor landscapes show that he was a competent draughtsman and colorist, and his sketches of animals and family members are particularly animated and lively. In encouraging his son to make artwork, Camille connected Georges with dealers and exhibitions and even offered to send him supplies:

Why don’t you try to make lithographs while you are with Felix, it’s no trouble and you know, it can be useful to you in any case here; it would keep you busy. Do you want me to send you paper and whatever else you need?

Georges was generally uncommunicative with his father, who begged him in letter after letter to relay updates on his life and work: “I don't understand why you don't give us any sign of life, we are very worried."

At times Camille mentions Lucien and his accomplishments—perhaps in an effort to inspire Georges to paint. He also details his own working practice, telling him of his successes and failures with specific paintings. This may have done the opposite of what Camille intended, making Georges feel inferior to his older brother, and intimidated by his accomplished father. As a reply to the above quoted letter, Georges responds:

I would be very happy if you would send me something to make a litho; I had thought about it but I was afraid of upsetting you. I will make a litho after Titi, you will indicate to me on the corner of the sheets of paper which side to use because I may be mistaken.

Georges takes his father’s suggestion to make work while he is with Felix (Titi) and tells his father the lithograph will be a portrait of his brother. It seems that, although Georges admitted he was fearful of Camille, he still sought guidance from his father.

Compositional Development

Several technical studies found that Camille started his paintings with an underdrawing in either solid or fluid charcoal.

Georges’s

Rue de l’Épicerie (fig. 3) is the only painting in the IMA study in which a charcoal underdrawing was observed in visible light and infrared (IR) photography. The possibility that light markings in charcoal are present in Camille and Lucien’s works cannot be discounted, as in some cases they may have been obscured by infrared-absorbent pigments in the paint layer above.

Figure 3: Front, visible light. Georges Manzana-Pissarro (French, 1871–1961), Rue de l’Épicerie, Rouen, 1898, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Holliday Collection, 79.283.

Figure 3: Front, visible light. Georges Manzana-Pissarro (French, 1871–1961), Rue de l’Épicerie, Rouen, 1898, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Holliday Collection, 79.283.

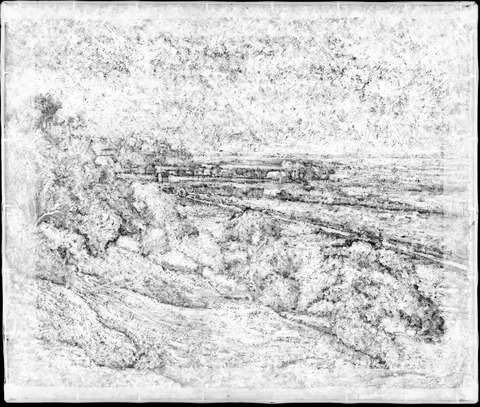

To plan his composition, Georges made small lines that summarily denoted the placement of objects, something Camille likely would have done in many of his works, although this practice was not observed in the IMA paintings.

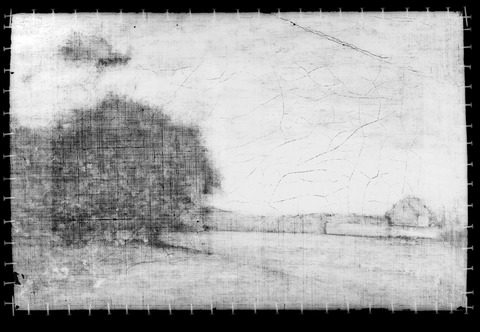

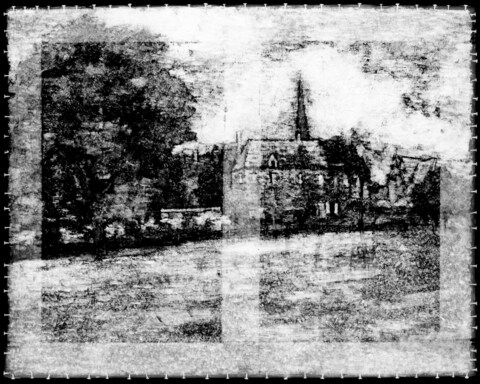

Georges then blocked in discrete swaths of color that did not overlap, leaving small gaps between the areas of color. This too mimicked Camille’s working process, except Camille would then build up the paint layers, adding detail and eventually filling in the spaces. This can be seen in all four of Camille’s paintings in the IMA, even his pointillist work,

House of the Deaf Woman. The X-radiograph illustrates this. Where there is a thinner application of paint between each element, the X-rays have passed through, leaving dark borders in the resulting image (figs. 4–6).

A comparison of Georges’s painting of the Rouen cathedral to that of his father, painted in the same year, shows the comparatively unfinished appearance of Georges’s relative to his father’s version (figs. 7–8 ). Although George’s

Rue de l’Épicerie may very well be a finished work, it shows us how his father’s initial blocking-in phase may have looked. Perhaps Georges’s lack of focus that so frustrated his father led him to abandon the painting prior to its completion.

Figure 4: X-radiograph. Camille Pissarro, Landscape, 1864, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of Mrs. Joseph E. Cain, 75.981.

Figure 4: X-radiograph. Camille Pissarro, Landscape, 1864, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of Mrs. Joseph E. Cain, 75.981.

Figure 5: X-radiograph. Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), The House of the Deaf Woman and the Belfry at Éragny, 1886, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Anonymous Gift, 2002.76.

Figure 5: X-radiograph. Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), The House of the Deaf Woman and the Belfry at Éragny, 1886, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Anonymous Gift, 2002.76.

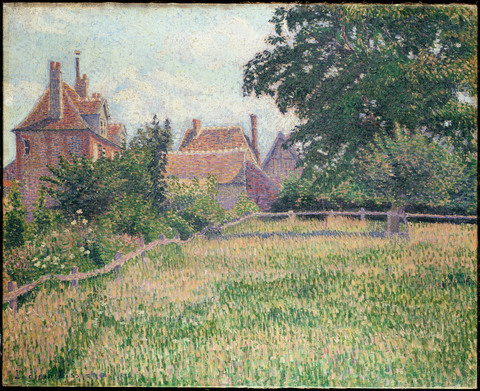

Figure 6: X-radiograph. Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Rye from Cadborough, Sunset, 1913, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Holliday Collection, 79.284

Figure 6: X-radiograph. Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Rye from Cadborough, Sunset, 1913, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Holliday Collection, 79.284

Figure 7: Georges Manzana-Pissarro (French, 1871–1961), Rue de l’Épicerie, Rouen, 1898, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Holliday Collection, 79.283.

Figure 8: Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), Rue de l’Épicerie, Rouen (Effect of Sunlight), 1898, oil on canvas, 32 × 25-5/8 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Mr. and Mrs. Richard J. Bernhard Gift, 1960, 60.5.

In Lucien’s

Rye from Cadborough and

Interior of the Studio, the same spaces between elements of the composition are visible in the X-radiograph, indicating that Lucien built up his paintings in a similar way to his father and brother, blocking in the initial forms of each compositional element before building up the layers of paint. Previous studies found that Camille and Lucien’s charcoal underdrawings were often emphasized by a dark blue French ultramarine outline.

French ultramarine underpaintings were indeed found in both of Lucien’s works from the IMA collection as well as in two of the four paintings by Camille:

House of the Deaf Woman and

Woman Washing Her Feet in a Brook. The earlier of Camille’s works in the IMA grouping,

Landscape and

The Banks of the Oise at Pontoise, do not have blue underpaintings.

French ultramarine was used widely by the Impressionists. Because of its high tinting strength, it was frequently used as a replacement for black in the color palette.

Impressionists believed that black was not found in nature—it was not considered a spectral color and represented the absence of light. Although Cézanne is quoted as saying Camille stopped using blacks by 1865, Camille and other Impressionists did in fact use it sparingly.

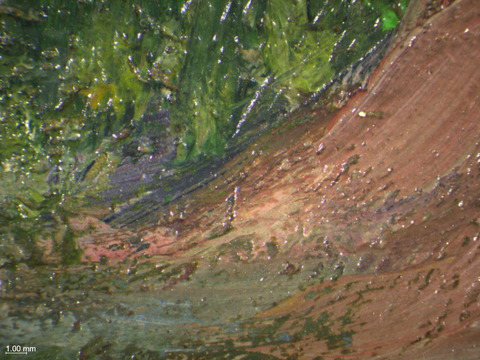

Camille’s planning process was fluid and recursive. He painted with French ultramarine directly onto the ground to outline forms. He would then often rework the composition, continuing to use the same blue pigment to denote compositional changes on top of the paint layers. This process can be seen in

Woman Washing Her Feet in a Brook as well as in

Woman Bathing her Feet in a Brook at the Art Institute of Chicago, for which the IMA work is an

étude, or study (fig. 9).

Figure 9: Photomicrograph showing French ultramarine outlining over paint layers, visible light. Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), Woman Washing Her Feet in a Brook, 1894, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of George E. Hume, 48.17.

Figure 9: Photomicrograph showing French ultramarine outlining over paint layers, visible light. Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), Woman Washing Her Feet in a Brook, 1894, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of George E. Hume, 48.17.

A French ultramarine outline is seen both above and below paint layers in Lucien’s

Rye from Cadborough as well

. However, this technique, which appears to have served the practical purpose of marking changes in Camille’s work, is used to aesthetic effect by Lucien. Lucien painted the line over paint layers to emphasize the contours of the hills, rather than to denote changes (fig. 10). He also appears to have deliberately left open spaces between design elements to show the initial blue underpainting. Lucien’s outlining shows influences of his printmaking practice, where each passage of color has a hard-edged dark outline made by the key plate. Blue outlining can also be seen in works of his contemporaries such as Van Gogh, who Lucien befriended in 1886.

Figure 10: Photomicrograph of French ultramarine brushstroke over paint layer, visible light. Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Rye from Cadborough, Sunset, 1913, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Holliday Collection, 79.284.

Figure 10: Photomicrograph of French ultramarine brushstroke over paint layer, visible light. Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Rye from Cadborough, Sunset, 1913, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Holliday Collection, 79.284.

While Camille made changes as he painted, Lucien appears to have been more methodical. He would allow the undesired elements of the painting to dry and then completely repaint the passages. This process was observed in Lucien’s

Interior of the Studio (fig. 11) and in

Rade des Bormes (1923) (fig. 12)

Figure 11: Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Interior of the Studio, 1887, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift in memory of Robert S. Ashby by his family and friends, 1995.100.

Figure 11: Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Interior of the Studio, 1887, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift in memory of Robert S. Ashby by his family and friends, 1995.100.

Figure 12: Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Rade de Bormes, 1923, oil on canvas, 54.2 × 65.9 cm. The Courtauld Institute of Art, Courtauld, Samuel; gift; 1932, P.1932.SC.321. Image copyright: © The Samuel Courtauld Trust.

Figure 12: Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Rade de Bormes, 1923, oil on canvas, 54.2 × 65.9 cm. The Courtauld Institute of Art, Courtauld, Samuel; gift; 1932, P.1932.SC.321. Image copyright: © The Samuel Courtauld Trust.

In

Interior of the Studio, Lucien initially painted his brother Georges in a slightly different position and with different objects on the table to the left. From what can be seen in the X-radiograph, the original composition adhered very closely to the smaller

Coin d’Atelier (fig. 2) presumably painted before the IMA work. The original composition was outlined in a blue underpainting as usual, but interestingly, the outline of the reworked composition was painted in red. The red underdrawing can clearly be seen in the macro-scanning X-ray fluorescence (MA-XRF) image for mercury, which is indicative of a vermilion pigment (fig. 13). As luck would have it, this element is easily detectable by XRF and gives us a very clear, beautiful illustration of Lucien’s style of contouring. The linear, fluid lines that can be seen in the scan are likely what Camille’s underpaintings would have looked like as well. The use of a red underpainting is unique in Lucien’s body of work. He presumably used this color to signal to himself the new placement of compositional elements. The red would have stood out against the relatively cool color palette of the fully completed prior composition and the blue outline, which would likely not have been covered by the paint layers above. The blue outline was later obliterated with dabs of orange paint (fig. 14). Lucien emphasized the red outline over the final paint layers, making it a design element itself, just as he would do later in

Rye from Cadborough (fig. 15).

Figure 13: MA-XRF scan for mercury (Hg). Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Interior of the Studio, 1887, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift in memory of Robert S. Ashby by his family and friends, 1995.100.

Figure 13: MA-XRF scan for mercury (Hg). Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Interior of the Studio, 1887, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift in memory of Robert S. Ashby by his family and friends, 1995.100.

Figure 14: Photomicrograph showing fully painted knee covered up with complementary color, visible light. Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Interior of the Studio, 1887, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift in memory of Robert S. Ashby by his family and friends, 1995.100.

Figure 14: Photomicrograph showing fully painted knee covered up with complementary color, visible light. Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Interior of the Studio, 1887, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift in memory of Robert S. Ashby by his family and friends, 1995.100.

Figure 15: Photomicrograph showing dark red stroke under paint layers, and lighter cool-toned red stroke over paint layers, top of chair. Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Rye from Cadborough, Sunset, 1913, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Holliday Collection, 79.284.

Figure 15: Photomicrograph showing dark red stroke under paint layers, and lighter cool-toned red stroke over paint layers, top of chair. Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), Rye from Cadborough, Sunset, 1913, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, The Holliday Collection, 79.284.

The Courtauld study concluded that Camille and Lucien’s different ways of handling pentimenti show that, for Camille, painting was a continuous creative process involving reworking and revisiting and that “Lucien does not appear to have been as rigorous – in comparison his works are much less reworked, and one feels he tried to realize them in one or two sittings."

However, the fact that Lucien did not make changes as he painted or return to his paintings as often as his father, does not necessarily mean his practice lacked rigor. Lucien’s handling of pentimenti probably came from his early influence as a pointillist painter, which required that the artist avoid blending paint in order to keep each dot of color distinct. In fact, we see in

House of the Deaf Woman, which was painted using the pointillist technique, that Camille also waited for the layers to dry before adding the figure on the right (fig. 16).

Figure 16: Photomicrograph of figure in foreground showing wet-over-dry technique, visible light. Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), The House of the Deaf Woman and the Belfry at Éragny, 1886, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Anonymous Gift, 2002.76.

Figure 16: Photomicrograph of figure in foreground showing wet-over-dry technique, visible light. Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), The House of the Deaf Woman and the Belfry at Éragny, 1886, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Anonymous Gift, 2002.76.

Unlike his son, whose early influence was molded by the strict rules of pointillism, Camille’s loose method follows from his start as an Impressionist painter. It wasn’t in Camille’s nature to continue with pointillism as it wasn’t “rapid enough and does not follow sensation."

Camille’s painting method was one of continuous creativity, but he was also unsure and frustrated at times. Camille in particular revisited the series of women washing their feet, writing to Lucien on 22 November 1894:

As soon as I have something, I will send it on to you. I have something which I think will be satisfactory, a Little Peasant Girl Soaking Her Feet [903], but it will have to lie around [in the studio] for the present; although it is finished, it lacks—well, something! I do think I will get it right, I feel that I will!

He painted

Woman Washing Her Feet in a Brook and

Woman Bathing her Feet in a Brook in multiple campaigns, painting wet-in-wet until the surface was so built up that many passages appear muddled and gray. Lucien’s more methodical planning arguably resulted in cleaner colors. In

Rye from Cadborough, he avoided mixing on the canvas by leaving a space between each element and working with a loaded brush. He likely also mixed on the palette rather than on the surface of the painting, which is typical of the Post-Impressionists, in contrast with the working methods of the Impressionists.

Surface and Substrate: Mattness and Absorbent Grounds

The Pissarros preferred their paintings to have a matte appearance, as did many of their contemporaries. Impressionists considered matte colors truer to life, mimicking the observed surface texture of objects found in nature. The painter’s choice to display a matte painting was also an ideological stance, a sign of modernity, and thus a rejection of traditional Academic painting. For display at the Academy’s Salon exhibitions, the final step in the completion of a painting was to apply a glossy varnish.

The subtle colors of Impressionist paintings would be made saturated and highly keyed if a glossy varnish were to be added on top. Contrasting color, emphasized by varnish, was associated with the teachings of the Academy, where instruction was conducted indoors and under the illumination of candlelight. This resulted in dramatic chiaroscuro.

This was not the desired aesthetic of

plein air painting embraced by the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists.

Camille is known to have varnished his early works, and in 1878 he wrote to Eugene Murer, “I am going to recommend the dealer not to varnish except with a colourless varnish."

Camille made the distinction to apply specifically a transparent varnish presumably because dealers were known to apply tinted varnishes to paintings to help them sell, sometimes adding bitumen to add the desired warm glow.

The tinted varnish tempered the bright colors, but its glossiness also signified to the collectors that the painting was a finished work. Probably knowing dealers' disposition to appease collectors, Camille recommended glazing paintings as an alternative, and has been attributed with introducing Post-Impressionist artists to the practice of glazing their paintings.

Lucien also disliked varnishing, and labels can be found on some of his paintings, attached to the back by his wife Esther, that read:

It was Lucien Pissarro’s invariable experience that in any of his pictures he allowed to be varnished, the values were all changed and the picture spoilt—the harm increasing as the varnish darkened. Whereas those pictures left unvarnished retained all their original freshness. The above applies equally to the work of his father, Camille Pissarro.

The sentiment conveyed by this label captures the Pissarros' concern that the delicate color harmonies of their paintings would be thrown off by the inevitable yellowing of varnish.

Mattness was not only achieved by eliminating varnish. Impressionists and Post-Impressionists considered the final surface quality of their works before laying down a stroke of paint. One of the ways to achieve this is with a technique called

peinture à l’essence, in which the tube paint was squeezed out onto blotting paper that would absorb some of the oil and remove some natural gloss of the paint.

Another way to manage the gloss of the paint was at the canvas preparation stage. An absorbent priming layer could wick away oil from the paint layers, leaving the painting with a matte surface.

In artist’s manuals, absorbent grounds were recommended because they were thought to leave the colors more vibrant, pure, and long-lasting. They included different recipes for chalk and glue grounds (some including oil, soap, or wax).

Recipes for chalk and glue grounds were suggested as preparation for stage flats and decorations.

In fact, there was a general interest in decorative arts among the Impressionists and especially Post-Impressionists, and many used decorative art techniques in their fine art practice.

Artists could buy canvases already prepared with absorbent grounds as well. Léonor Mérimée’s 1839 manual cites a colorman, “Mr. Rey,” as the first to prime canvases with absorbent grounds.

An 1878 Windsor and Newton catalogue lists something called a “half-primed ground,” and later a 1905 Lefranc et Cie manual lists a “semi-absorbent ground."

During a brief period in the late 1880s when Camille and Lucien were experimenting with pointillism, they used absorbent grounds that differ from the grounds found on their works of other periods. In the IMA’s collection of Pissarro family paintings, all except for

House of the Deaf Woman and

Interior of the Studio have grounds composed of lead white in oil. This ground was typical of the pre-primed, commercially produced canvases available.

However, scanning electron microscopy / energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) on samples of the grounds of

House of the Deaf Woman and

Interior of the Studio found that both paintings were primed with a mixture of chalk and glue that is characteristic of an absorbent ground.

The reason for this choice may have been that pointillist paintings required the small dabs of paint to dry before the next layers were applied. An absorbent ground was recommended by Mérimée because “the time required for priming may be shortened very much,” and thus it would follow that the drying time of the upper layers of paint would also decrease.

However, some artists did not like this quality. For example, in an 1887 letter to Lucien, Signac complained that the oil medium stained the ground and sank on drying. That same year, Seurat tried using another type of ground called a plaster ground, but he was unhappy with the results.

Previous research speculated, based on documentary and empirical evidence, that Lucien and Camille had used glue and chalk grounds for their pointillist paintings. For example, in an unpublished 2011 dissertation from the Courtauld Institute of Art, the author observed that in Lucien’s pointillist work

The House of the Deaf Woman, Éragny (1886) (fig. 17) a “chalky and brittle ground, leanly bound and poorly adhered to the support” was present. The author concluded that this ground was consistent with the documented evidence of Lucien and Camille’s “preference for leanly bound semi-absorbent primings made of chalk and glue."

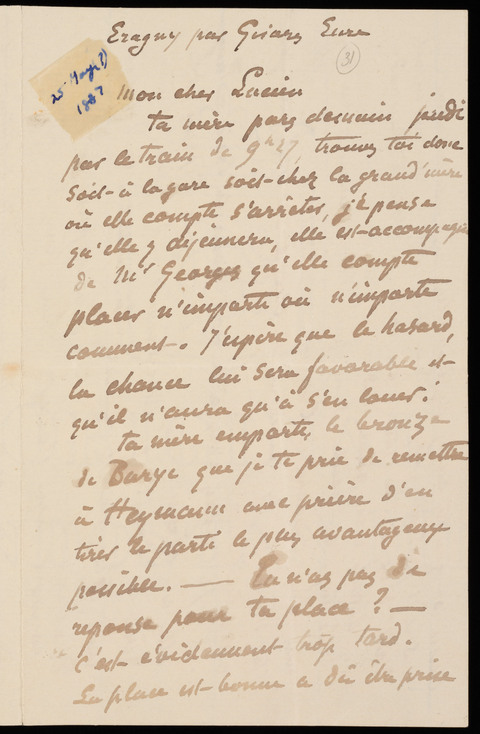

In many technical and art historical studies, a letter written on 25 May 1887 is used as evidence for Camille’s use of absorbent grounds:

Figure 17: Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), The House of the Deaf Woman, Éragny, 1886, oil on canvas, 58 × 72 cm. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Presented by Esther Pissarro, 1951, WA1952.6.6.

Figure 17: Lucien Pissarro (French, 1863–1944), The House of the Deaf Woman, Éragny, 1886, oil on canvas, 58 × 72 cm. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Presented by Esther Pissarro, 1951, WA1952.6.6.

I had written to you in a hurry about Tanguy’s canvas, it is awful and second-rate; I ask you to tell Contet to send me something to cover a size thirty square canvas, the size of my square stretcher, with enough excess material to nail it on well. A fine canvas with white plaster. A layer very thin, very thin.

In this letter, Camille asked Lucien to acquire a canvas for him to fit a stretcher he already had in his possession. The priming described appears to be an absorbent ground, particularly of the plaster variety (See Camille’s original handwritten letter, figs. 18, 19).

Figure 18: Letter from Camille to Lucien, 25 May 1887. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Box File 1887 No. 427 (25 May) Paris.

Figure 18: Letter from Camille to Lucien, 25 May 1887. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Box File 1887 No. 427 (25 May) Paris.

Figure 19: Letter from Camille to Lucien, 25 May 1887. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Box File 1887 No. 427 (25 May) Paris.

Figure 19: Letter from Camille to Lucien, 25 May 1887. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Box File 1887 No. 427 (25 May) Paris.

The use of the word “plaster” in this quote is glossed over in most scholarly literature. The word may simply refer to the matte appearance and absorbent qualities of the material. “Plastery” (

plâtreuse) was often mentioned as a descriptor for the varnish-free surface of Impressionist paintings.

Vincent van Gogh ordered a canvas “prepared with plaster” in 1888, later theorizing in one of his letters that it was composed of “pipe clay,” a term for kaolin.

However, plaster and chalk are chemically different materials. Plaster is calcium hydroxide, which is more soluble in water, while chalk is calcium carbonate. Although a plaster will eventually convert into calcium carbonate by reacting with carbon dioxide in the air, the materials would react differently in the application process: plaster would solidify into a film with the addition of water, while calcium carbonate would require a binder to cure. In his 1839 manual, Mérimée didn’t use the terms interchangeably; his recipe for an absorbent ground called for either plaster

or chalk.

In a 1990 study, authors explored the possibility that Camille was referring to the use of actual plaster of Paris in the above letter, stating that “the white pigment seems to have been plaster, which is hydrated calcium sulphate."

The manual of John Cawse (1840) contains a recipe for an absorbent ground, which included whiting and size made with parchment clippings.

He stated that “Plaster of Paris” may be used or incorporated with the size and whiting, noting it was the “same coating now used by the gilders of frames."

However, analysis of the two pointillist works in the IMA collection found only calcium, no sulfur. Later, in 1921, Nabis painter Paul Sérusier advocated for the use of a ground comprised of either

blanc d’Espagne, which is chalk, or

plâtre éteint bound with glue in his short treatise,

ABC de la peinture.

Plâtre éteint was plaster made of quicklime, also known as slaked lime, rather than that made of gypsum, or calcium sulfate. It may be that the plaster ground that Camille requested was shorthand for

plâtre éteint.

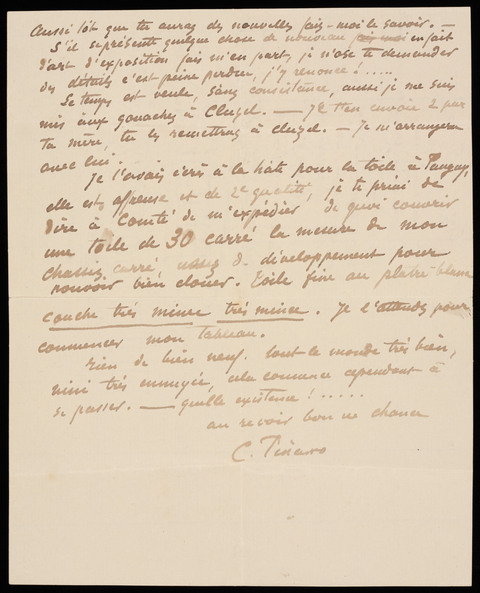

Just ten days prior to the above letter, Camille asked that Lucien obtain a canvas prepared with a plaster ground from supplier Troisgros for him:

Can you get a size 20 canvas if it’s square, and I’ll bring you one prepared with plaster, because I’ll have them made that way, if Troisgros will give it to me on loan, otherwise we’ll have to prepare them ourselves; but where to buy the canvas and how to pay for it?

Again, a plaster ground (

plâtre in the original French) is specified (see Camille’s original hand-written letter, fig. 20). Crucially, this letter shows that not only did father and son share materials, techniques, and theories metaphorically, but also literally. Thread count analysis by professor Don H. Johnson found that the canvases of

Interior of the Studio and

House of the Deaf Woman match, meaning the two canvases were cut from the same roll of fabric.

These matching canvases serve as physical evidence for what is indicated in the letter.

Figure 20: Letter from Camille to Lucien, 15 May 1887. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Box File 1887 No. 423 Sunday (15 May) Paris.

Figure 20: Letter from Camille to Lucien, 15 May 1887. Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Box File 1887 No. 423 Sunday (15 May) Paris.

The letters detailing Camille’s materials shopping list confirm that the Pissarros were making particular requests from their suppliers, not simply buying the preprepared materials advertised in colormen’s catalogues. The letters demonstrate that, if pressed, they were willing to prepare the absorbent grounds themselves. There is no supplier stencil on

House of the Deaf Woman, and

Interior of the Studio is lined so the supplier of the canvas could not be determined. Likewise, the stretchers display no supplier’s marks.

There is a chance the canvases could have come from a supplier who did not mark his canvases. For example, Tanguy (mentioned in Camille’s 25 May 1887 letter) was known not to have applied a supplier’s stencil on the canvases he sold. He ran a small shop in Paris out of which he lived and worked, hand-grinding pigments himself.

The lack of a supplier’s canvas stencil may imply that the canvases of

House of the Deaf Woman and

Interior of the Studio were artist-stretched and prepared. The supplier of the canvases would likely have been French, as Lucien and Camille usually acquired supplies locally, and they were both working in Éragny at the time these works were painted. However, the possibility that the canvases are English cannot be excluded, as at times Camille made requests of Lucien when he was in England.

Mattness could be attained in the painting stage as well with the addition of white. The overall pale or “blond” appearance attained by adding white unified the bright color palette of Impressionist paintings. This technique was called

peinture claire and was meant to depict the bright light observed when painting outdoors.

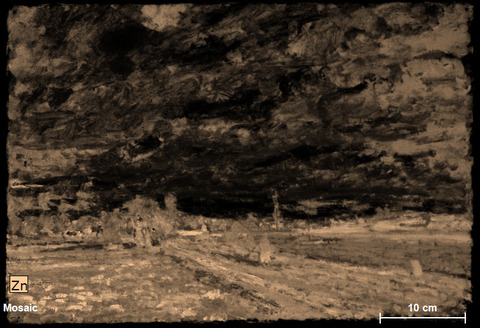

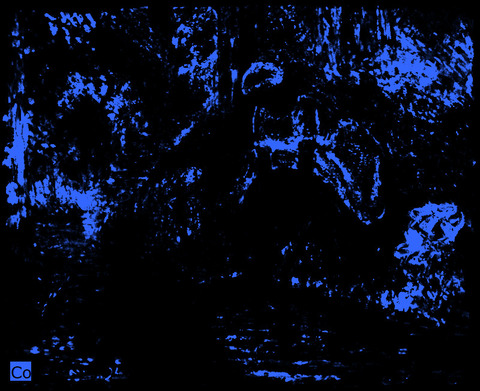

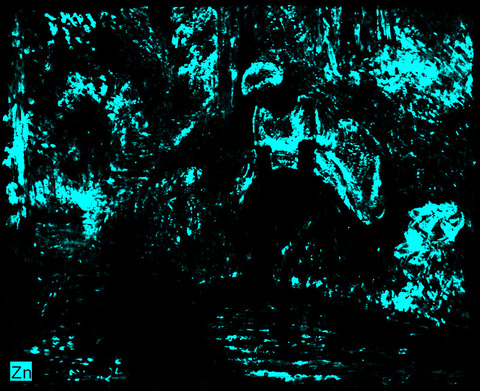

The Banks of the Oise near Pontoise displays a palette muted by the addition of white: both lead and zinc white are present throughout the painting (See the MA-XRF map for zinc, fig. 21).

Woman Washing Her Feet in a Brook has a passage of cobalt blue paint that may have been manufactured as a mixture with zinc white, as the MA-XRF maps for cobalt and zinc overlap perfectly (fig. 22). In the 1880s, Pissarro requested colors “on a base of zinc” from his supplier Contet.

The addition of zinc white would have given the colors greater opacity and a light, matte appearance. In Lucien’s

Rye from Cadborough, the overall palette is unified by paint mixtures containing lead white and chrome yellow to render the colors lighter and more opaque. Georges used lead white in the majority of his paint mixtures throughout

Rue de l’Épicerie, contributing to an overall light, chalky appearance.

Figure 21: MA-XRF map for zinc (Zn). Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), The Banks of the Oise near Pontoise, 1873, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, James E. Roberts Fund, 40.252.

Figure 21: MA-XRF map for zinc (Zn). Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), The Banks of the Oise near Pontoise, 1873, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, James E. Roberts Fund, 40.252.

Figure 22: MA-XRF maps for cobalt (Co) and zinc (Zn), visible light. Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), Woman Washing Her Feet in a Brook, 1894, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of George E. Hume, 48.17.

Figure 22: MA-XRF maps for cobalt (Co) and zinc (Zn), visible light. Camille Pissarro (French, 1830–1903), Woman Washing Her Feet in a Brook, 1894, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of George E. Hume, 48.17.

Recommendations for Future Research

While this study sought to reveal a more thoughtful understanding of Georges’s creative role in the family, limited evidence—both documentary and in terms of artworks—left us with a somewhat vague view of his contributions. Analysis of more works by Georges would facilitate a better understanding of his painting practice as a whole. In the future, thread count analysis on other Pissarro paintings could link more canvases to one another: in particular, Camille’s

View from My Window (1886–1888) at the Ashmolean Museum could be analyzed, which was started at the same time as his

House of the Deaf Woman and is the same size. It would be useful to undertake medium analysis on the Pissarro paintings speculated to have been primed with absorbent grounds to confirm the use of this preparation for their pointillist works. A MA-XRF scan of Lucien’s

Interior of the Studio from the back of the canvas could determine whether the same colors were used in the smaller

Coin d’Atelier, whose composition appears to be reflected in the earlier underpainting. This artistic family unit is exceptional in the context of art history. It is hoped that, in the future, paintings by other members of the Pissarro family will be studied, which would allow for additional material connections to be made between multiple generations.

Conclusion

The Pissarro works in the collection of the IMA at Newfields tell a story of collaborative exploration and artistic experimentation. The discourse between Camille and his sons allows for a poignant look at their personal and creative relationship. Previous studies of the Pissarros have emphasized the influence of Camille on the art of his sons. This study has revealed a more complex relationship. While Camille certainly endeavored to bestow his artistic knowledge on his sons, there was a flow of information and inspiration back and forth between Camille and Lucien. They relied on one another to bring projects to fruition, whether that be through collaboration, for example Lucien’s publishing projects, or by obtaining materials for one another. The intriguing discovery that Lucien and Camille’s pointillist canvases come from the same roll of fabric confirms that the two artists quite literally shared materials. Camille’s encouragement of Lucien eventually blossomed into a discussion between artistic and intellectual equals. They exchanged ideas on current aesthetic philosophy, materials, and techniques, as well as politics. While Lucien thrived in the presence of his father, Georges appears to have become withdrawn. It cannot be denied that Camille had a strong influence on Georges throughout his early adulthood. His paintings mirror those of his father, and

Rue de l’Épicerie is no exception, displaying a clear Impressionistic style. The planning and execution of this work show that Georges was a careful and sensitive painter. Camille and Georges also shared materials: both father and son’s Rouen paintings were painted on canvases from Contet, possibly acquired at the same time,

and Camille sent Georges paper to make his lithographs.

It seems Georges tried to live up to his father’s expectations while Camille was alive, but after Camille’s death, Georges turned to a completely different genre of painting. He painted works inspired by Orientalism and made decorative objects. It is hard to say why, but it is possible that he only felt free to explore his own interests when detached from his father. In a way, each brother had what the other lacked. Lucien was a very methodical painter, and Georges was free-spirited and always sought inspiration. Therefore, Camille endeavored to impart to Lucien a spirit of experimentation while urging Georges to take on a more rigorous artistic practice. Each son reacted differently to their father’s opinions—either interpreting them or eventually rebelling against them.

Notes

doi: 10.58609/2.1

Link Copied