OVERVIEW

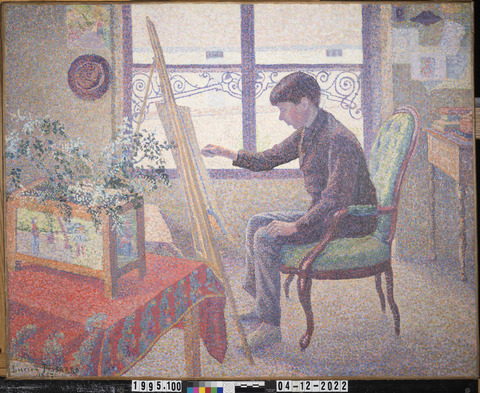

Identification number: 1995.100

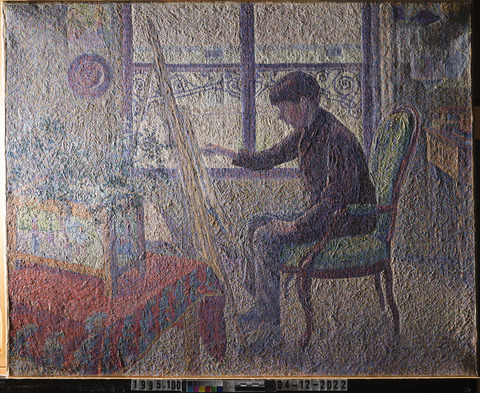

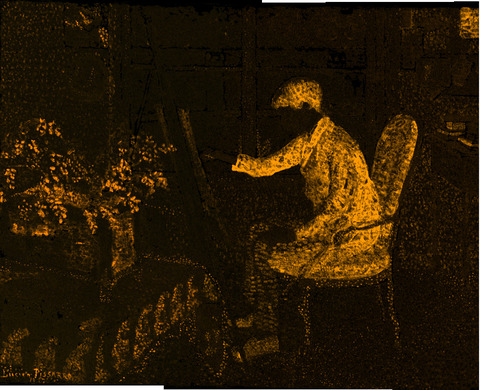

Artist: Lucien Pissarro

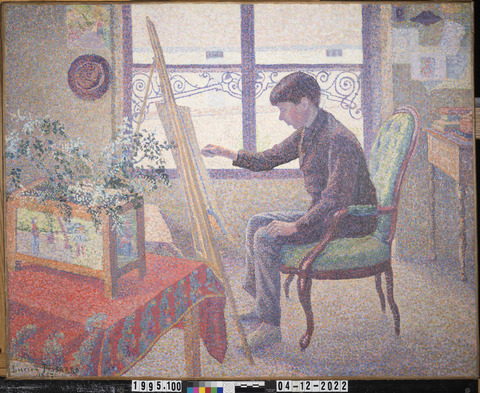

Title: Interior of the Studio

Materials: Oil on canvas

Date of creation: 1887

Dimensions: 64.1 × 80 cm

Conservator/examiner: Alex Chipkin with contributions from Dr. Gregory D. Smith and Laura Mosteller

Examination completed: 2022

Distinguishing Marks

Front:

Back:

There are minimal markings or inscriptions on the back of the painting. Brown paper tape covers half the width of the stretcher bars on all four sides. The tape extends over the tacking margins and the front of the painting. A lining canvas covers the back of the canvas. The only inscriptions visible are the IMA’s accession number, “1995.100,” seen on the top-right corner in red; a number written on a paper label in the middle of the top horizontal member; and number “65” printed on an orange piece of paper attached to the right vertical member. There are also remnants of red wax seals on the stretcher (zoom into fig. 2 to see inscriptions).

Historical Context

In 1884, the Pissarro family moved from Pontoise to Éragny-sur-Epte, where Interior of the Studio would be painted three years later (fig. 3). Lucien’s painting career began around this time, and he lived in this house on and off until he made a permanent move to England in 1890. Although Lucien was inclined toward painting from a young age, his mother, Julie, wanted a practical career for her son. He was first sent to Paris to work as a clerk and then to London in 1883 to live with his uncle Phineas Isaacson and learn English. Julie thought this would benefit a possible future career in business. He would later return to London around 1887 at the age of 24 to apprentice at a printing press, and in 1894, he founded his own press, called the Eragny Press after Éragny-sur-Epte.1

In this painting, Lucien depicts his brother Georges, then aged 16, at an easel inside the Pissarro house where his father had a studio on the second floor. The window’s vertical mullion cuts the composition in half. On the left is a table with a jardiniere on top crowded together with an easel, while on the right, the composition opens, and the focus is on the back-lit boy. Outside the window, one can just make out the linear structure of the wall that sectioned off the garden from the neighbour’s house beyond. It looks out on the same scene depicted in Camille’s The House of the Deaf Woman and the Belfry at Eragny, painted just a year earlier in the same location (fig. 4). Some of the objects in the room are known. The hat hanging on the wall on the left is Camille’s. Camille also made the tiles depicting peasants picking apples, which are set into the jardiniere on the table.2 There is also photographic documentation of the chair, which was brought to Camillle’s next studio, as well as the iron bars of the shallow balcony outside the window.3

The entire painting is made of small dots in the Pointillist style. In 1885, Lucien met Georges Seurat and Paul Signac in the studio of Armand Guillaumin, a painter and friend of Camille’s. They shared thoughts on divisionism, derived from new scientific theories like simultaneous contrast and local versus spectral color. Lucien took up their methods of using dots of paint to construct his paintings. The following summer, he worked alongside Signac in Le Petit Andelys, an area not too far from Éragny. Lucien later introduced his father to the two artists, and Camille too began to work in the Pointillist style.4 Lucien effectively employed the theory of simultaneous contrast in Interior of the Studio. He depicts the soft, orange-yellow light entering through the window, while everything else is cast in cool blue shadow. The dim room is punctuated by the vibrant red of the tablecloth on the left and the green chair on the right.

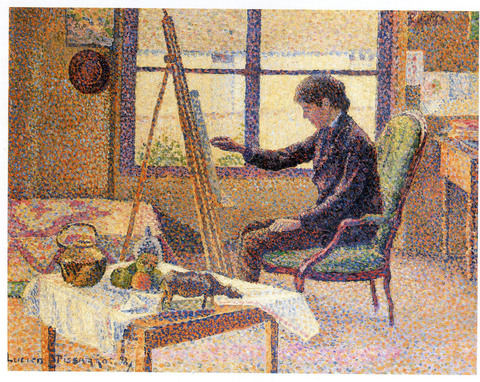

The painting has four preparatory works associated with it. There are three drawings and one painting, Corner of the Studio (Coin d’atelier) (fig. 5). The composition is very similar to that of the IMA work except for one notable difference. In this painting, the table is placed further to the right blocking Georges’s leg. It is covered with a white tablecloth instead of red, and on it sit a copper tea pot, vase, bowl of fruit, and a ceramic cow. The ceramic cow remained in the family and appears in a photograph of Lucien’s daughter Orovida.5 Without the tall jardiniere, the table in the background is made more visible. In the IMA work, Lucien has also shortened Georges’s hair, extended the legs of the chair, and added more papers pinned to the wall on the right-hand side.

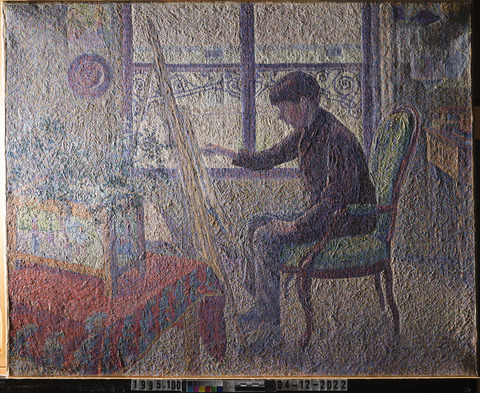

Summary of Treatment History

Before its acquisition by the IMA in 1995, the painting was first assessed by private conservator Zahira (Soni) Veliz at Sotheby's in London. Veliz stated that the canvas seemed “moderately brittle” and was probably glue or glue-paste lined. She noted slight distortions on the upper-left corner. She observed that the ground and paint layers seemed stable, aside from the losses “concentrated in the lower left quadrant, in the background just above and to the right of the figure's head.” She noted minor flake losses throughout the canvas. The heat and pressure of the lining “slightly altered” the surface texture of the paint. She noted retouching along the top edge, just above the easel. She observed that the dark green pigments on the left side of the picture extinguish in ultraviolet light, but concluded they were likely not overpaint. She described the upper coating as “a moderately thin and discoloured glossy layer applied overall” and concluded that it was natural resin varnish, based on its fluorescence. Underneath was what she described as “a dark, grayish brown layer” that she posited was surface dirt and nicotine. The peaks of the impasto appeared to be free of dirt, which she theorized was probably removed during the lining process.6

Before being transported to the IMA, the vulnerable areas of lifting paint were consolidated and faced with tissue by private practice conservator Nicole Ryder.7 Once the painting came to the museum, it was discovered to be in worse condition than had been previously believed. David Miller observed more instability, lifting, and cleavage of the paint layer.8

According to Miller’s condition report, he first removed the tissue and then consolidated the paint layer using 10% gelatin and a warm tacking iron. He described the cleaning and removal of prior retouching in detail, which was done in four steps. Triammonium citrate removed the very dark black/gray surface dirt on top of the varnish. Removal of the thick discolored yellow-brown varnish was undertaken with a gel comprising xylene, benzyl alcohol, water, Ethomeen C12 and Carbopol 394. The gel was effective in cleaning the coating from the interstices of the impasto, as well as the previous retouching. Miller noted, “There was a tremendous amount of dirt and grime in the paint surface, below the varnish, indicating that the picture had originally ben unvarnished and had accumulated all of this dirt prior to restoration, lining, and varnishing by a later hand.” A 3% soap solution was used to remove this layer. A minor amount of dirt was left on the surface, as Miller was unable to clean it. The painting was then consolidated another time with gelatin.

After cleaning, Miller believed that the painting appeared too “raw” and dull, so the painting was first coated with Acryloid B-72 applied with a brush, and then given another coat of the same varnish, this time sprayed on. Areas that were considered too glossy were made more matte by lightly abrading the surface with an eraser.9 Retouching was undertaken mostly in the wrought ironwork and the chimneys. They were filled with a commercial filler and retouched with Lefranc and Bourgeois Restoration Colors.

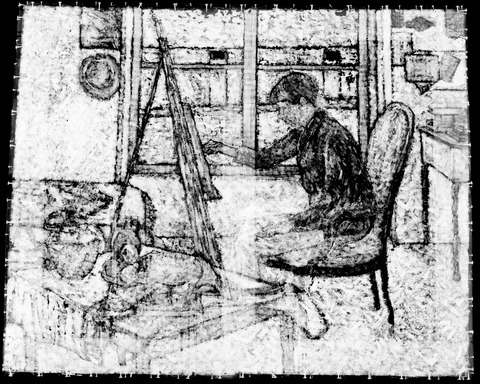

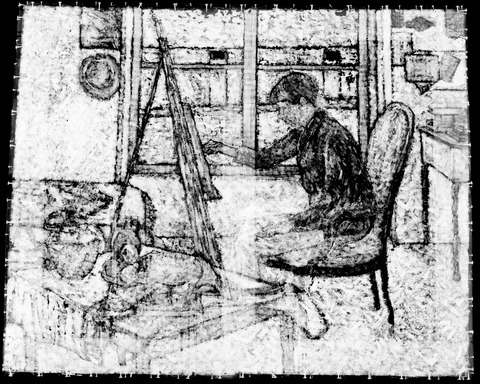

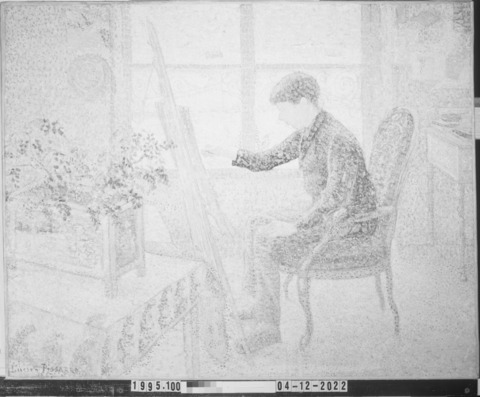

During the 1996 treatment of this painting, a different composition was found by X-radiography (fig. 6). It was discovered that Lucien had initially painted the table as shown in his earlier sketch. The composition underneath is almost identical to that of Corner of the Studio (Coin d’atelier), described in the Historical Context section above. David Miller suspected this during his assessment, as he observed the paint had different texture and more instability in the lower-left corner.10

Current Condition Summary

The painting is overall in stable condition. The lining canvas adds support, keeping the canvas in good plane. The ground and paint layers appear to be well bound. There is craquelure throughout the paint surface, as is expected for a painting of this age with its treatment history. As was observed in the Summary of Treatment History section, there is minor flattening of the impasto, likely due to the heat and pressure associated with the lining process. Minor losses throughout the painting have been inpainted in the prior treatment.

Methods of Examination and Imaging

| Examination/Imaging | Analysis (no sample required) | Analysis (sample required) |

|---|---|---|

| Unaided eye | Dendrochronology | Microchemical analysis |

| Optical microscopy | Wood identification | Fiber ID |

| Incident light | Microchemical analysis | Cross-section sampling |

| Raking light | Thread count analysis | Dispersed pigment sample |

| Reflected/specular light | X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) |

| Transmitted light | Macro X-ray fluorescence scanning (MA-XRF) | Raman microspectroscopy |

| Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence (UV) | ||

| Infrared photography (IR) | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) | |

| Infrared transmittography (IRT) | Scanning electron microscope -energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) | |

| Infrared luminescence | Other: | |

| X-radiography |

Technical Examination

Description of Support

The work is painted on a plain-weave linen canvas (untested) with a 27.8 × 31 per cm thread count.11 It has been lined with a similar weight canvas. The painting, which measures 64.1 × 80 mm, is likely a number 25 figure format (81 × 65mm) turned horizontally by the artist.12 Thread counting analysis by Professor Don H. Johnson found that the painting’s support matches to that of The House of the Deaf Woman and the Belfry at Eragny by his father Camille, painted just a year earlier.13 The thread match suggests that each canvas was cut from the same bolt of fabric.

Auxiliary Support:

Original Not original Not able to discern None

Attachment to Auxiliary Support:

The painting is mounted on a five-member stretcher with mortise and tenon joints at the corners and vertical member. The patina of the stretcher indicates that it is probably original to the painting. As conservator Zahira Veliz noted in her initial assessment of the painting before it was acquired by the museum, “The relined painting seems to have been restretched onto its original stretcher after lining."14 There are 10 stretcher keys present, all of which have been replaced, made of a lighter colored wood than the stretcher. The keys are not secured to the stretcher bars.

Condition of Support

Aside from slight corner draws on the upper and lower right-hand side corners, the support is planar and in stable condition. The tacking margins remain intact.

Description of Ground

Color:

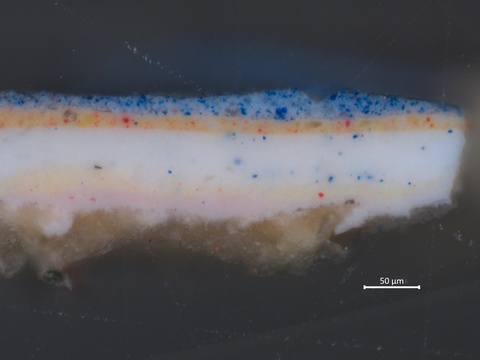

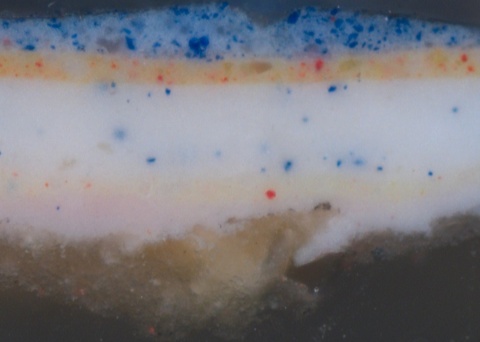

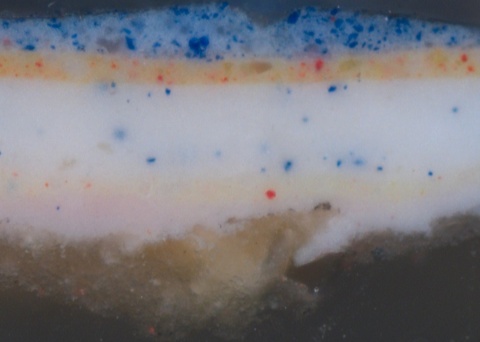

Translucent beige (fig. 7)

Application:

Thickness:

The ground is applied in a very thin layer, about one quarter of the thickness of the paint layers above.

Materials/Binding Medium:

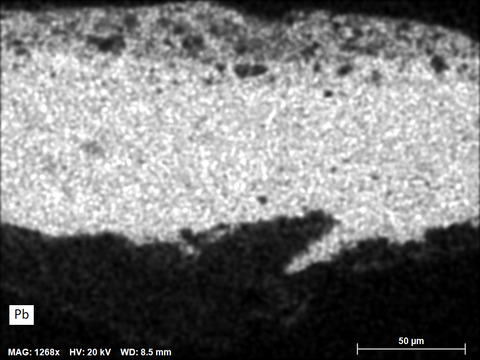

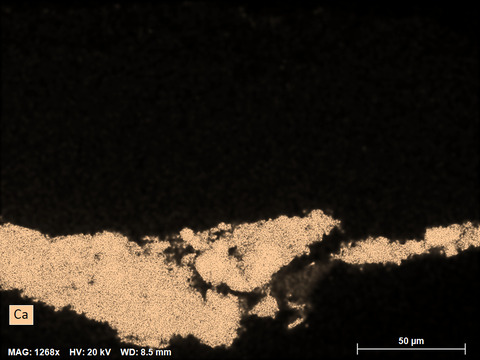

The ground is composed of chalk and glue. Calcium was detected with SEM-EDX, indicating a chalk priming layer (figs. 9–11). Gelatin medium was confirmed with FTIR analysis.15

Sizing:

Likely gelatin (untested)

Character and Appearance (Does texture of support remain detectable/prominent?):

Condition of Ground

Despite a history of flaking in isolated areas, overall, the ground appears to be well bound to the canvas.

Description of Composition Planning

Methods of Analysis:

Surface observation (unaided or with magnification)

Infrared photography (IR)

X-radiography

Analysis Parameters:

| X-Ray equipment | GE Inspection Technologies Type: ERESCO 200MFR 3.1, Tube S/N: MIR 201E 58-2812, EN 12543: 1.0mm, Filter: 0.8mm Be + 2mm Al |

|---|---|

| KV: | 25 |

| mA: | 3.0 |

| Exposure time (s) | 90 |

| Distance from x-ray tube: | 36 in |

| IRR equipment and wavelength | Modified Nikon D610 camera with a Coastal Optics lens and X-nite 1000C filter |

Medium/Technique:

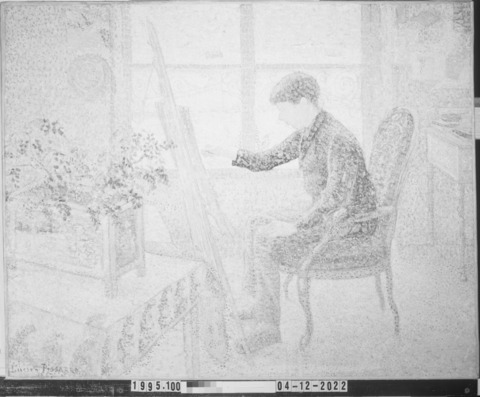

Lucien laid in the main compositional elements of this painting with medium-sized brushstrokes separated by a space between. This initial underlayer can be observed in the X-radiograph, where the distinct black borders indicate passages where the paint was thinner, which allowed the X-rays to pass through (see fig. 6). A similar method of laying down the initial composition was consistently used by his father Camille. For example, it can be seen in his Pointillist work, The House of the Deaf Woman and the Belfry at Eragny, painted just a year prior. However, Lucien’s brushstrokes are not as large and sweeping as those of his father. As with his father’s painting, an underdrawing for the initial composition could not be discerned by infrared photography (fig. 13).16

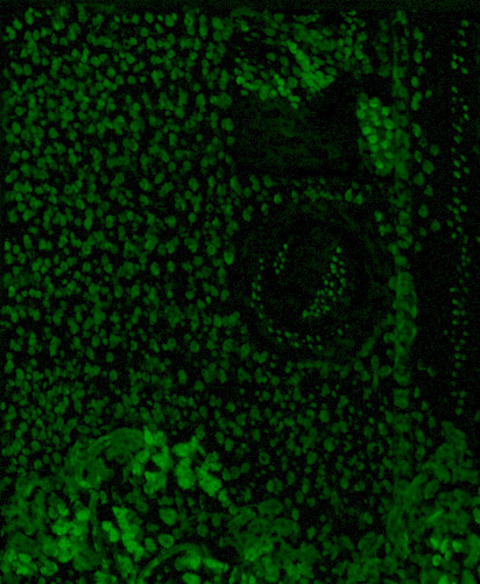

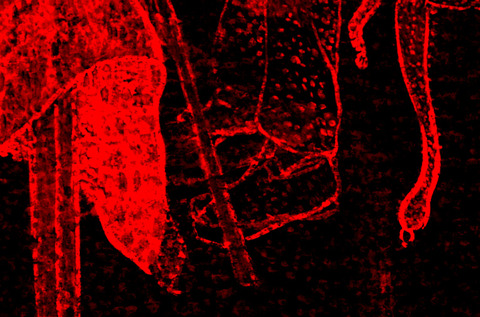

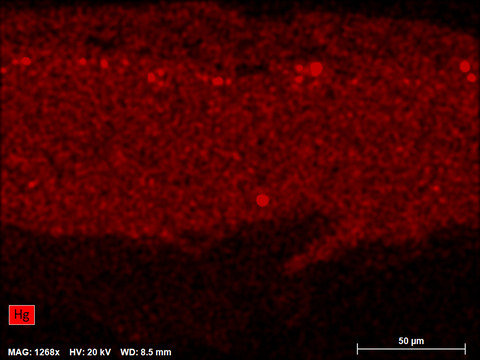

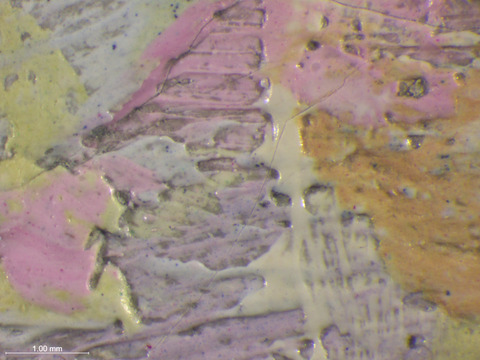

However, once Lucien finished the initial painting, he did make an underpainting to lay out all the changes that are now visible. The MA-XRF scan for mercury (fig. 14), which is indicative of vermilion, clearly shows the extensive red underpainting (see fig. 9). The scan not only shows the extent of the underpainting, but the technique used. The brushstrokes are linear and painted in a fluid medium, the lines tapering off at the ends. This color is unusual, as the Pissarros' planning stage was typically undertaken in a fluid French ultramarine (fig. 15), which can be seen in other Pissarro works in the IMA collection such as Woman Washing her Feet in a Brook by Camille and Rye from Cadborough, Sunset by Lucien. Red was probably chosen to make the new guidelines more easily discernible over the veil of predominantly cool-colored dots. The vermilion paint also contains some bone black, as confirmed with Raman spectroscopy.

As can be seen in Lucien’s Rye from Cadborough in the IMA collection, it seems he used the underdrawing as an element of the painting itself, allowing it to peek out between the upper paint layers (fig. 7).

Description of Paint

Analyzed Observed

Application and Technique:

Lucien applied the paint in two or three stages, allowing each layer to dry in between. The larger areas such as the back wall, sky, and floor were started with hatched strokes. This can be observed in both raking light and in the X-radiograph (see fig. 6). Lucien used a similar technique to block in the sky in Rye from Cadborough. The rest of this initial layer was painted using fairly linear brushstrokes that conform to the shapes of the elements and were painted wet-in-wet (fig. 16). These brushstrokes were used for Georges’s body, chair, window mullions, jardiniere, easel, and the table on the right-hand side (seen in raking light) (fig. 17). These brushstrokes were also used for the original table (seen in raking light extending from the corner of the current table to the boy’s foot).

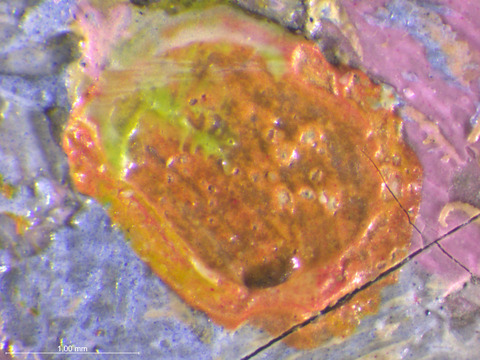

The green paint may have been one of the first colors applied, as the brushstrokes are very evenly spaced and well organized. The MA-XRF scan for copper makes clear that the paint strokes on the upper-left corner are painted in rows. Subsequent colors are more densely packed and applied in a random manner, seemingly filling in the spaces. This can be seen, for example, in the MA-XRF scan for cobalt (fig. 20).

Pentimenti:

Painting Tools:

Binding Media:

Oil paint (untested)

Color Palette:

Overlapping MA-XRF maps for copper and arsenic indicate the warm green used for the chair and the decoration on the jardiniere was painted using emerald green (fig. 25). The same green pigment was also dabbed into the decoration on the tablecloth as well as darker, shadowy areas like the boy’s clothing, hair, and the back wall.

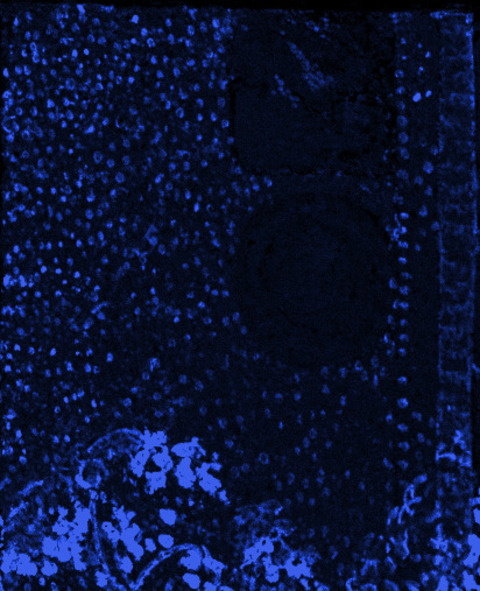

The cooler green used for the leafy plant in the jardiniere is a mixture of emerald green and cobalt blue. The MA-XRF map for cobalt indicates that in much of the blue shadows, cobalt blue was used (fig. 26). A second blue in the shadowy areas, such as the blue used for the hat, is French ultramarine. This was confirmed with Raman spectroscopy on dark blue particles in the uppermost layer of Sample a (see fig. 7).

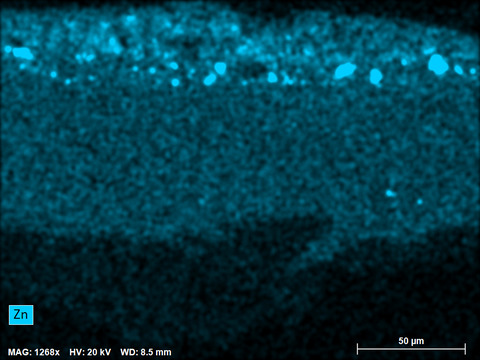

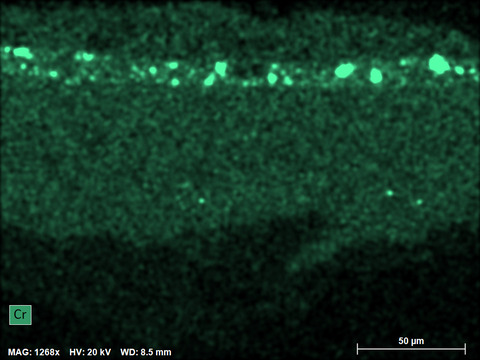

For the dabs of orange in this painting, Lucien used zinc yellow and vermilion. Sample a was analyzed with SEM-EDS, which indicated that the yellow particles in the orange layer beneath the blue layer is zinc yellow. This was indicated by the presence of zinc and chromium, the SEM-EDS maps of which overlap precisely. This pigment was preferred by his father Camille Pissarro, who in October 1885 recommended Seurat use it in his reworking of La Grande Jatte.17

In the same orange layer of Sample a, SEM-EDS found mercury in the red pigment particles, which is indicative of vermilion (figs. 27–30). This same mixture was used in orange dabs of paint in the reworking of La Grande Jatte.18 The mixture was found in Camille’s The House of the Deaf Woman and the Belfry at Eragny as well. It was likely used by all three artists to depict Fénéon’s notion of “solar orange,” a term used to describe the particular hue of afternoon light.19

Condition of Paint

There are small losses throughout the painting on the lower-left and upper-right corners. Many losses are concentrated on the borders of the initial composition. They likely occurred in passages where the paint did not properly adhere. The areas of loss can be seen in the infrared luminescence image as well as under ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence (figs 34, 35).

Description of Varnish/Surface Coating

Analyzed Observed Documented

| Type of Varnish | Application |

|---|---|

| Natural resin | Spray applied |

| Synthetic resin/other | Brush applied |

| Multiple Layers observed | Undetermined |

| No coating detected |

Condition of Varnish/Surface Coating

As mentioned in the “Summary of Treatment History” section, after the cleaning of this painting in 1996, Chief Conservator David Miller applied a both a brush and spray varnish coating of Acryloid B-72 and mattified the coating with the use of an eraser. The fluorescence of the synthetic varnish can be observed in the ultraviolet-induced fluorescence image below (fig. 35). The work looks appropriately matte, which would have been Lucien’s preference.20 Posthumously, Lucien's wife attached a label indicating to future stewards of his paintings not to apply varnish.21

Description of Frame

Original/first frame

Period frame

Authenticity cannot be determined at the time/ further art historical research necessary

Reproduction frame (fabricated in the style of)

Replica frame (copy of an existing period frame)

Modern frame

Frame Dimensions:

Outside dimensions: 78.9 × 94.9 cm

Rebate dimensions: 65.7 × 81.6 cm

Sight size dimensions: 63.5 × 79.4 cm

Rail width: 7.6 cm

Distinguishing Marks:

N/A

Description Of Molding/Profile:

The frame is a passe-partout flat profile with a raised squared border at the outer edge and a cavetto at the sight edge. Made from poplar wood, it has 45-degree miter joinery in the corners (fig. 38).

>Figure 38: Frame, front detail. Lucien Pissarro, Interior of the Studio, 1887, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift in memory of Robert S. Ashby by his family and friends, 1995.100.> Figure 38: Frame, front detail. Lucien Pissarro, Interior of the Studio, 1887, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift in memory of Robert S. Ashby by his family and friends, 1995.100.

Figure 38: Frame, front detail. Lucien Pissarro, Interior of the Studio, 1887, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift in memory of Robert S. Ashby by his family and friends, 1995.100.

Condition of Frame

The frame is structurally secure, and the painted finish is in excellent condition.

ADDITIONAL NOTES OR COMMENTS

The painting was accessioned to the IMA’s collection in 1995 and underwent conservation treatment in 1996. Paintings Conservator David Miller wrote in a memorandum, “A painted neoimpressionist frame based on the type used by the Pissarro family was designed and fabricated at the IMA to replace the existing gilt frame."22 A workorder from Miller to the Exhibits department was sent on 30 August 1996.

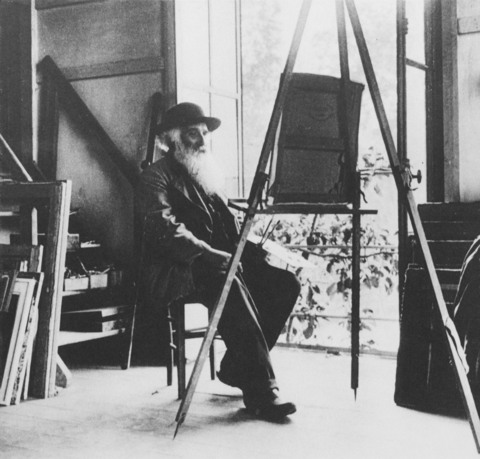

In notes for a presentation at the time of the work’s first display in the IMA’s Neo-Impressionist galleries, Miller wrote, “Although no direct evidence has been found to date as to what the frame on ‘Interior of the Studio’ looked like when it first exhibited in 1887, the collaborative decision was made to put it in a white frame with the profile based upon a photograph of Camille working in the same Eragny studio (as seen in our painting) showing a stack of frames on the floor, including a single white one (fig. 39). The frame was designed by this Conservator, fabricated by the museum carpenter out of poplar, and was given six coats of gilder’s gesso by the conservation technician. Test panels were painted with Liquitex colors and were viewed against the painting in the neo-impressionist gallery, under the correct lighting. The color selection of a slightly warm yellowish tone was made by the Chief Curator and the Conservator. The frame was then painted with the correct tone and was ‘antiqued’ with rottenstone in 2% matte soluvar in mineral spirits.” 23

In a letter to chief curator Ellen Lee, Joachim Pissarro, chief curator at the Kimball Art Museum, wrote, “I am happy to hear that you have taken the initiative to replace the Louis XIV frame with a simpler one, more in keeping with what we know of Lucien’s preference."24

Notes

-

C. Harrison, J. Whiteley, and S. Shorvon, Lucien Pissarro in England: The Eragny Press 1895-1914 (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2011), 36–39. See also W.S. Meadmore, Lucien Pissarro (London: Constable and Company, 1962), 40–41, for detailed description of the Pissarro family’s financial hardships from 1887 to 1890. ↩︎

-

See Sotheby’s, Modern British and Irish Paintings, Drawing and Sculpture: London Wednesday 22nd November 1995 (London: Sotheby’s, 1995), lot 15, 22. For images of the tiles, see numbers 1665, 1666, 1667, and 1668 in Ludovic-Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pisssarro: Son Art – Son Oeuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1939), pl.312. ↩︎

-

J. Pissarro and C. Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings (Milan: Skira; Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 2005), 3:499. ↩︎

-

See Anne Thorold, A Catalogue of the Oil Paintings of Lucien Pissarro (London: Athelney Books, 1983), 4 and plate 10, and W.S. Meadmore, Lucien Pissarro, (London: Constable and Company, 1962), 40, J. Rewald, ed., Camille Pissarro: Letters to His Son Lucien (Boston: MFA Publications, 2002), 63–64. ↩︎

-

Anne Thorold, ed., The Letters of Lucien to Camille Pissarro 1883–1903 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 87. ↩︎

-

Z. Veliz, “Condition Report: Portrait of Georges Pissarro in Camille Pissarro's Studio, signed and dated 1887, oil on canvas, 64 x 80 cm. Relined., London,” 1995, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

D. Miller, “Re: Pissarro,” 5 and 8 December 1995, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

D. Miller, “Addendum to Condition Report of Zahira Veliz,” 30 October 1996, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Pink Pearl 101 eraser composed of vulcanized vegetable oil, rubber, pumice, and coloring agents. ↩︎

-

D. Miller, Treatment Report, (September 27, 1996), Conservation Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art ↩︎

-

D.H. Johnson, “Thread Count Report: Interior of the Studio Lucien Pissarro 1887 (T19/1995.100) from the Indianapolis Museum of Art,” April 2022, p. 1, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

See Bourgeois âinè’s 1888 table of ready-stretched canvases reproduced in D. Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: National Gallery in association with Yale University Press, 1991), 46. ↩︎

-

D.H. Johnson, “Canvas Match Report: Camille Pissarro, Lucien Pissarro PS827, T19 from the Indianapolis Museum of Art,” April 2022. ↩︎

-

Z. Veliz, “Condition Report: Portrait of Georges Pissarro in Camille Pissarro's Studio, signed and dated 1887, oil on canvas, 64 x 80 cm. Relined., London,” 1995, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

The sample was treated with hydrofluoric acid vapor to shift spectral interferences from the chalk and enhance the visibility of spectral bands from the binding medium. ↩︎

-

Dark linear strokes seen in the IR image are likely associated with the vermilion underdrawing, as it contains some carbon from bone black, which absorbs in the near infrared region. ↩︎

-

J. Kirby, K. Stonor, A. Roy, A. Burnstock, R. Grout and R. White, “Seurat’s Painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology,” The National Gallery Technical Bulletin 24 (2003): 25, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/media/15500/kirby_stonor_roy_burnstock_grout_white2003.pdf. ↩︎

-

Inge Fiedler. “A Technical Evaluation of the Grande Jatte.” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 14, no. 2 (1989): 177, https://doi.org/10.2307/4108750. ↩︎

-

See J. Gage, “The Technique of Seurat: A Reappraisal,” The Art Bulletin 69, No. 3 (September 1987): 449. ↩︎

-

Anthea Callen, Anthea Callen, “The Unvarnished Truth: Mattness, ‘Primitivism’ and Modernity in French Painting, c. 1870– 1907,” The Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 738–746. ↩︎

-

After his death, Esther L. Pissarro, Lucien’s wife, often attached a printed label to his paintings that read, “It was Lucien Pissarro’s invariable experience that in any of his pictures he allowed to be varnished, the values were all changed and the picture spoilt—the harm increasing as the varnish darkened. Whereas those pictures left unvarnished retained all their original freshness. The above applies equally to the work of his father, Camille Pissarro.” This quote was transcribed from a photograph of the back of Village d’Eragny (1885) by Camille Pissarro reproduced in Anthea Callen, “The Unvarnished Truth: Mattness, ‘Primitivism’ and Modernity in French Painting, c. 1870– 1907,” The Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 740. ↩︎

-

David Miller, Memorandum to the Development Department of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, 17 January 1997, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

David Miller, notes for speech at Second Century Society dinner, 11 October 1996, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Letter from Joachim Pissarro to Ellen W. Lee, 1 November 1996, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

Additional Images