OVERVIEW

Identification number: 79.284

Artist: Lucien Pissarro

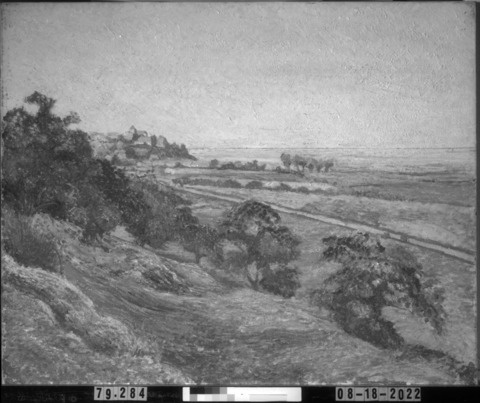

Title: Rye from Cadborough, Sunset

Materials: Oil on canvas

Date of creation: 1913

Previous number/accession number: TR3005

Dimensions: 53.5 × 64.5 cm

Conservator/examiner: Alex Chipkin

Examination completed: 2022

Distinguishing Marks

Front:

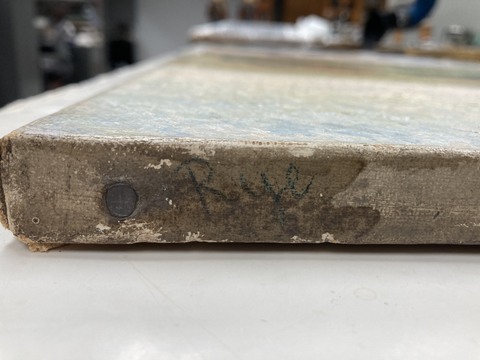

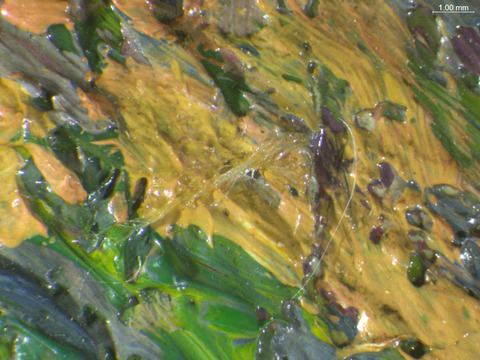

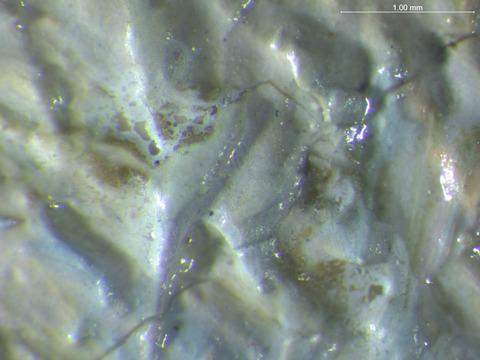

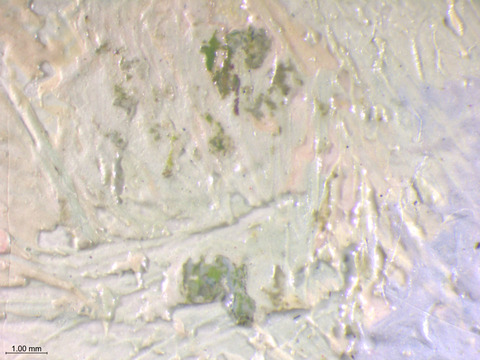

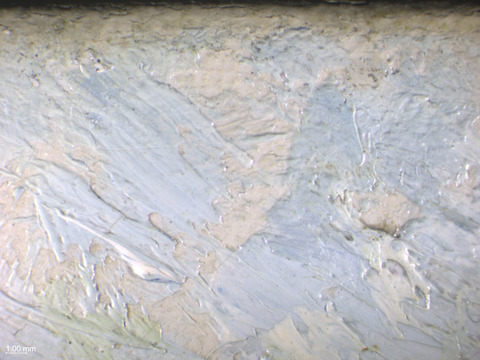

The artist’s monogram and the date “LP 1913” can be seen on the front of the painting on the bottom-right edge written in blue paint (figs. 1, 2). The signature is painted wet-over-dry, as can be seen in the photomicrograph below (figs. 1, 2), where the paint of the inscription skips over the texture of the dry paint beneath. There is also an inscription in blue on the top-right turnover edge that reads “Rye” (fig. 3).

Back:

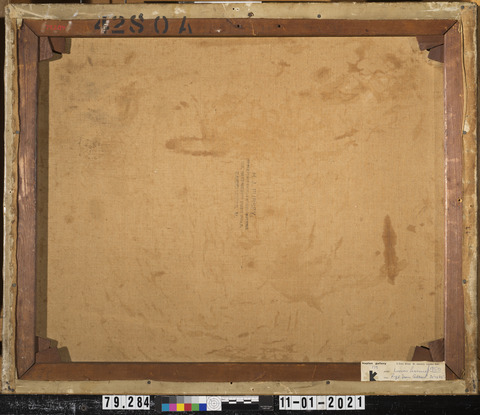

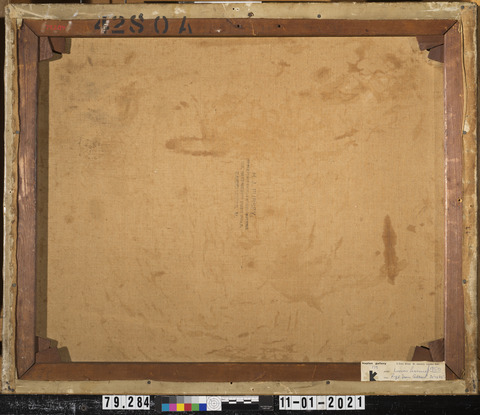

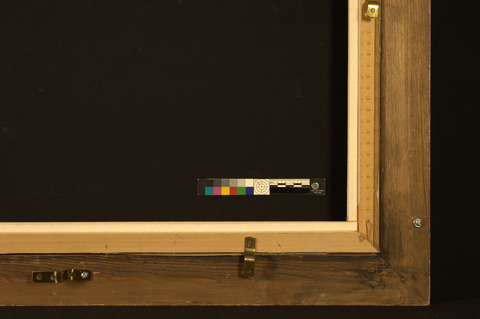

On the back, a stamp on the canvas denotes it is from the English artist supplier H. J. Pursey (zoom in to fig. 4 to see inscriptions). Various inscriptions are visible on the stretcher bars, including an inscription in graphite that reads, “Rye from Cadborough Sunset Aug 1913”. This inscription may have been written by the artist himself, as the handwriting looks similar to that on the front of the painting. There is a paper label from a gallery in London, Kaplan Gallery, attached to the bottom right-hand side of the stretcher.

Historical Context

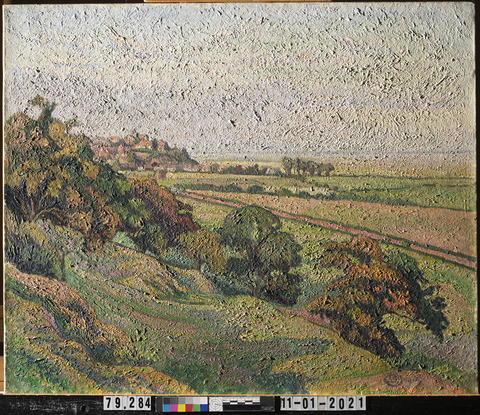

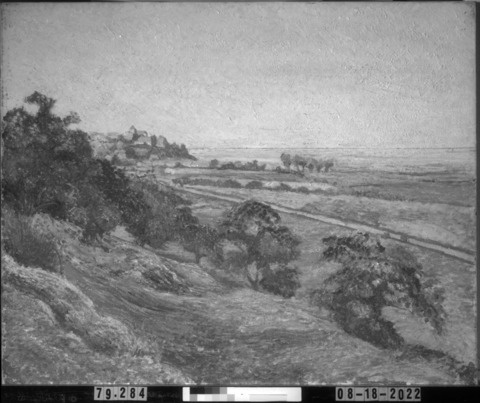

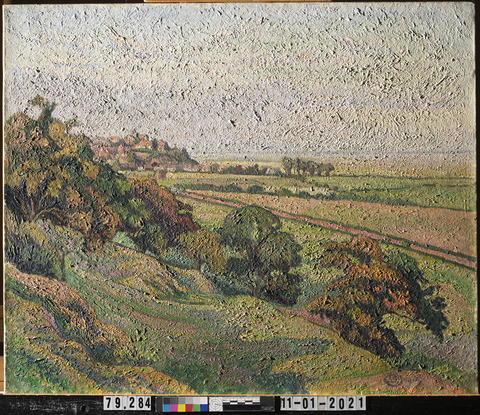

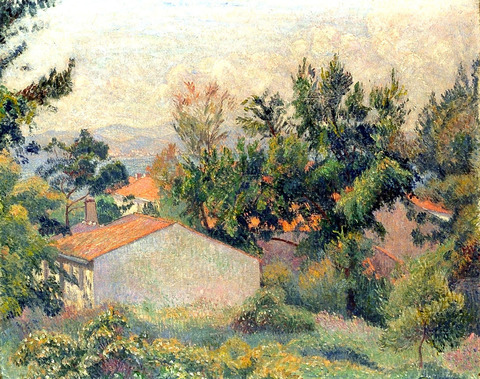

In Rye from Cadborough, Sunset, Lucien skillfully depicts the rolling hills of the English countryside at sunset (fig. 5). Warm evening sunlight skims the high points of the landscape. The brushstrokes sweep from left to right, conforming to the shape of each object. Stark diagonals emphasized by thick borders in deep green and blue paint draw the viewer’s eye to the stacked roofs on the hill in the distance. Although this work was painted 10 years after his father’s death, it exemplifies Camille’s enduring influence on Lucien. In this painting, Lucien attempts to capture the immediate sensation of this season and time of day. Lucien employed the theory of simultaneous contrast in his use of salmon pink alongside green in the fields dominating the landscape and the blue and yellow-orange that meet at the horizon. As discussed later, the manner in which Lucien built up the paint layers was also shaped by his father. Despite English influences on the Eragny Press,1 Lucien returned to a painting style more in keeping with French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in the early 20th century. His paintings even share some qualities with works by Van Gogh, who Lucien befriended in 1886.2

When Lucien painted this work, he had already been settled in England for 23 years. He lived alongside a circle of artists in west London, in a house he and his wife Esther called The Brook.3 As the inscription on the back of the painting suggests, Lucien was painting in southeast England in the medieval hilltop town of Rye in August of 1913. He decided to paint there while his wife, who was in bad health at the time, stayed with his mother Julie in France. Lucien lamented that he could not go with her, but felt that he could not waste any time, as he needed to produce paintings for an upcoming exhibition. He stayed there from the beginning of July to September in a house with two other artists, James Brown and J.B. Mason. His daughter Orovida, who herself desired to become an artist, also painted with them for part of the time.4

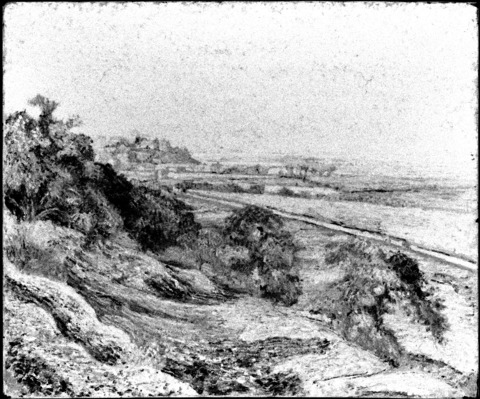

Lucien produced nine paintings in and around Rye that summer.5 Rye from Cadboro Cliff, Grey Morning (1913) depicts almost exactly the same view (fig. 6). The title of this painting provides more context for the IMA work: in both paintings Lucien faced east from Cadborough cliff, which is about one mile away from the Church of St. Mary in Rye; the wide spire of which is the tallest structure on the hill. The composition is strikingly similar to that of the IMA painting—it seems Lucien has simply positioned himself closer to the row of trees and to the right, to set Rye in the center of the composition, framed by green treetops. In 1914, Lucien would show three of his Cadborough paintings at the City Art Gallery in Leeds in their spring exhibition. Rye from Cadborough, Sunset, was one of the three exhibited.6

Summary of Treatment History

Chief Conservator Martin J. Radecki examined Rye from Cadborough, Sunset shortly after its acquisition in 1979. In his report, Radecki suggested that travel should be limited because “the fabric is becoming brittle.” He described the ground as a single, smooth, thin layer and theorized that it is a “proprietary oil type.” He noted that its condition was stable. Radecki posited that “the paint is an oil/resin type which has a vehicular paste consistency.” He observed that certain colors differ in solubility: the light colors were stable in MEK,7 and the dark greens and blues soluble in xylene.8 It was found in the 2022 conservation treatment that xylene did not, in fact, affect these colors (see below). In examining the surface coating, he observed a layer of synthetic, amber-colored varnish that was soluble in xylene, toluene, and propanol. Underneath the varnish there was a “moderate grime layer.” Radecki also noted the presence of minor retouching that was soluble in toluene.9

According to the treatment report, presumably written shortly after the examination report, Radecki removed the varnish with toluene. He did not remove the varnish in the passages that he noted in the examination report to be sensitive. It appears the surface dirt beneath the varnish was quite difficult to remove, requiring three passes of a soap, benzine, and water mixture.10 He described that the painting was “cleaned following design elements which went across the entire painting to alleviate the problems of unevenness.” Radecki noted sensitivity of the pinks in the sky when the “soap mixture” was used for the second time. After the dirt layer was removed, some “staining” remained on the surface of the painting. This likely refers to some minor transparent yellow marks in the sky. The painting was then varnished with 8% B-67 in xylene, applied with a brush. Radecki inpainted losses on the edges and “stained” areas of the painting with dry pigments in “PVA AYAB."11,12

In 1999, David Miller assessed the painting for loan to the Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale. The painting and frame were deemed to be in “excellent condition” and were given approval to travel.13

In 2021, Rye from Cadborough, Sunset underwent examination and treatment by Kress Paintings Conservation Fellow Alex Chipkin as part of the research for this catalog. Before treatment, the discolored varnish and imbibed dirt that had not been removed in the prior cleaning had muddled the bright colors in the sky. The varnish, which was brush-applied, had resulted in pooling in the interstices of the paint, making the valleys glossier than the peaks, which reflected light. Removal of the varnish was undertaken based on the historical evidence that it was not in keeping with Lucien’s preference for a matte surface quality. Further, B-6714 has more recently been found to age poorly, and so the varnish applied in the 1981 treatment was removed.15,16

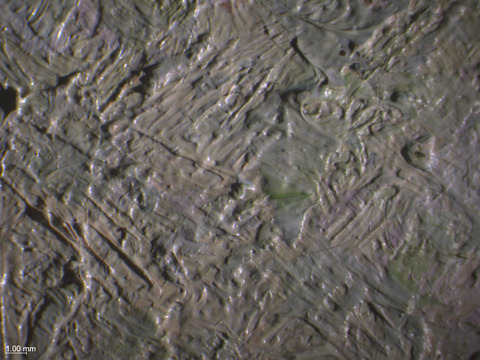

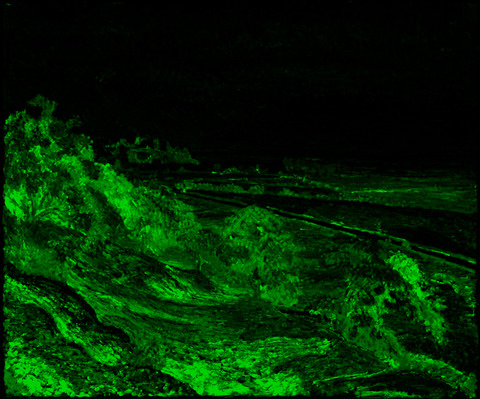

There were remnants of the prior varnish in the darker paint passages in the foreground, as well as some small areas in the sky, which were reduced. Cotton was embedded in the varnish in the foreground, observed under ultraviolet irradiation and in visible light under magnification (fig. 7). Radecki’s inpainting was observed on the upper-left and right-hand side corners in the ultraviolet irradiation, as well as in the MA-XRF scan for titanium, which indicated that the inpainting mixture contained titanium white (fig. 9) and, as Radecki described, covered over the “staining” (fig. 8). Radecki also appears to have inpainted out a splotch of green paint—which was likely transferred from another canvas close in time to the painting’s making (fig. 10). In the 2022 treatment, this splotch of green paint was left exposed as it reveals information about the artist’s technique.

Current Condition Summary

The painting is in stable condition. The canvas is taut, and the ground layer is well bound to the support. There are losses to the ground layer at all four corners of the painting. The paint layer exhibits no losses, and only minor age cracks. There are some minor drying cracks in passages where there is a thicker application of paint visible under magnification. The recent 2022 conservation treatment resulted in the removal of the glossy synthetic varnish. Colorimetry was conducted on three areas of the painting, which found that not only did removal of the varnish change the gloss of the painting, but also the colors (see fig. 11 for testing locations). For point #1 there was a ΔE shift of 3.19 towards red-blue. For point #2 there was a ΔE shift of 3.14 towards red-yellow, and for point #3 there was a ΔE shift of 2.05 towards green-blue.17 The painting now displays a matte appearance in keeping with the paintings of the period and Lucien’s own wishes that his paintings remain unvarnished.

Methods of Examination and Imaging

| Examination/Imaging | Analysis (no sample required) | Analysis (sample required) |

|---|---|---|

| Unaided eye | Dendrochronology | Microchemical analysis |

| Optical microscopy | Wood identification | Fiber ID |

| Incident light | Microchemical analysis | Cross-section sampling |

| Raking light | Thread count analysis | Dispersed pigment sample |

| Reflected/specular light | X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) |

| Transmitted light | Macro X-ray fluorescence scanning (MA-XRF) | Raman microspectroscopy |

| Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence (UV) | ||

| Infrared reflectography (IRR) | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) | |

| Infrared transmittography (IRT) | Scanning electron microscope -energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) | |

| Infrared luminescence | Other: | |

| X-radiography |

Technical Examination

Description of Support

Rye from Cadborough, Sunset is painted on a plain-weave linen canvas (untested) with a thread count of 15.2 × 15.3 threads per cm.18 The canvas measures 53.5 × 64.5 cm, which corresponds to the standard commercial number 15 (65 × 54 cm) canvas. The measurements indicate a vertical “figure” format oriented horizontally by the artist.19 The supplier stamp supports this, as it is located in the middle of the canvas and reads correctly when the painting is rotated 90º counterclockwise.

Auxiliary Support:

Original Not original Not able to discern None

Attachment to Auxiliary Support:

The painting is mounted onto a four-member stretcher with mitered corner joins. There are 30 evenly spaced tacks on the tacking margins and 11 on the back holding the canvas in place around the back of the stretcher.

Condition of Support

The canvas is unlined and holding in very good plane. It is slightly slack but in no immediate need of tensioning. All eight stretcher keys are present and are not secured to the stretcher bars.

Description of Ground

Materials/Binding Medium:

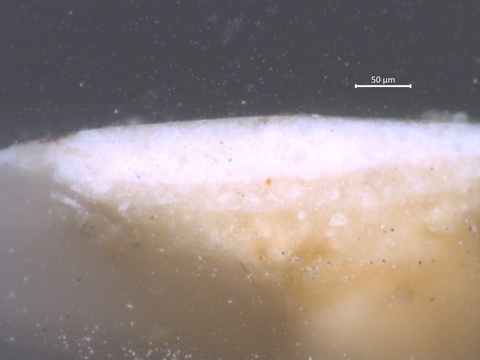

The ground is made up of three priming layers that can be distinctly seen in cross section (see Sample c, fig. 12). The first two layers are composed predominantly of calcium with a small amount of lead white and barium sulfate (figs. 13, 14). The uppermost layer, which appears as opaque and bright white in cross section, is composed of lead white with some small blue and black particles. During this period, most of Lucien’s grounds were composed of lead white, chalk, and bone black bound in linseed oil.20 The binding medium for the ground is likely a drying oil (untested). However, it has been documented that certain suppliers offered a ground with the initial priming layers composed of chalk and glue with a final layer of lead white.21 English supplier Windsor and Newton offered a “half primed” ground composed of glue and chalk in their 1897 catalogue. If purchasing a canvas prepared in this manner, artists were advised to apply another oil-bound layer themselves, composed of “lead white, chalk (2 parts lead white to 1 part chalk), a little linseed oil and some turpentine oil if thinning is required.” 22 This layer structure may suggest that Lucien bought a “half primed” canvas and, as instructed, added a final artist-applied ground layer.

Color:

Off-white

Application:

The ground extends to the edges of the canvas on the top and bottom. However, there is bare canvas on the left- and right-hand tacking margins. On those tacking margins, there are tack holes and cusping not associated with the current stretcher. This indicates that the canvas was primed on a different stretcher before being stretched onto the current one. Although bare canvas usually points to the painting having been primed and stretched by the artist, the fact that the canvas stamp is centered (as mentioned previously in the “Description of Support” section) and the ground extends to the edges of the canvas on the top and bottom indicate that it was likely prepared by the supplier.

Thickness:

The total ground layer is fairly thick, measuring about 130 micrometers. The two bottom layers together are ~80 µm thick, and the top layer is ~50 µm.

Sizing:

Likely gelatin (untested)

Character and Appearance (Does texture of support remain detectable/prominent?):

Despite the rough weave, the texture of the canvas is not readily visible through the ground layer. The multiple ground layers have created a very smooth paint surface (fig. 15).

Condition of Ground

Aside from losses at all four corners of the painting, the ground layer is well bound and shows no signs of cleavage from the canvas or paint layers above.

Description of Composition Planning

Methods of Analysis:

Surface observation (unaided or with magnification)

Infrared photography (IR)

X-radiography

Analysis Parameters:

| X-Ray equipment | GE Inspection Technologies Type: ERESCO 200MFR 3.1, Tube S/N: MIR 201E 58-2812, EN 12543: 1.0mm, Filter: 0.8mm Be + 2mm Al |

|---|---|

| KV: | 25 |

| mA: | 3.0 |

| Exposure time (s) | 120 |

| Distance from x-ray tube: | 36” |

| IRR equipment and wavelength | Modified Nikon D610 camera with a Coastal Optics lens and X-nite 1000C filter |

Medium/Technique:

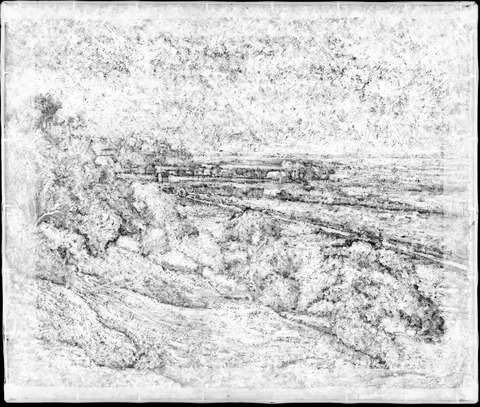

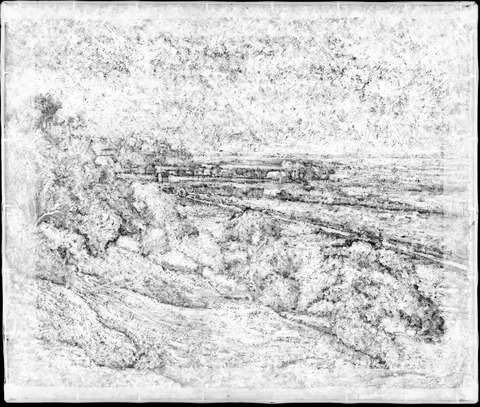

Lucien started this painting with an underpainting that functioned as a preparatory drawing in fluid blue. His father used the same technique (fig. 16).23 The blue paint used for the underdrawing is synthetic ultramarine, as was found in other paintings by Lucien.24 In-situ Raman spectroscopy confirmed the presence of ultramarine in the paint used for the underdrawing. The only possible carbon-based underdrawing visible is a straight horizontal line denoting the horizon line in the distance (fig. 17).

Description of Paint

Application and Technique

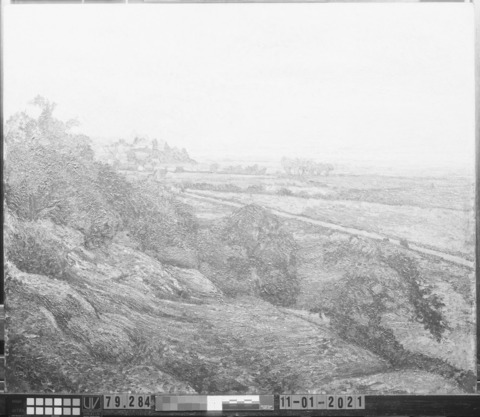

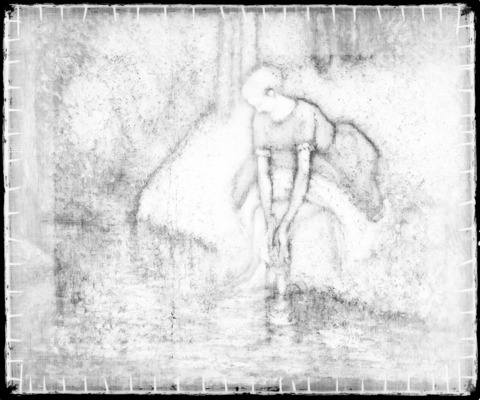

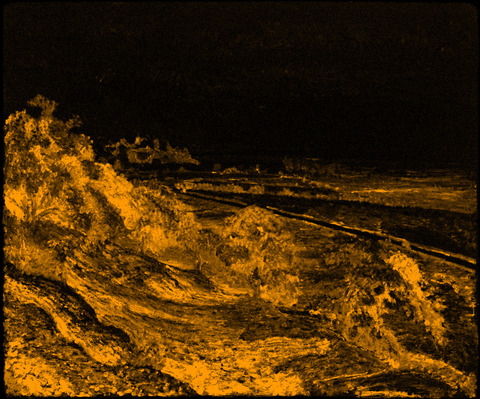

It appears that Lucien painted most passages of this work around the same time. After the blue underdrawing was dry, he painted within the confines of these lines, leaving a narrow space of ground and the underpainting showing between. This can also be observed in the painting’s X-radiograph (fig. 18). The same can be seen in the X-radiographs of all of the IMA’s Camille Pissarro paintings. See, for example, the X-radiograph of Woman Washing Her Feet in a Brook, painted in 1894 (fig. 19).25

The paint was blocked in following the confines of the underdrawing (fig. 20). The colors within these confines were blended wet-into-wet on the surface of the canvas. Because of the space left between each element, the colors did not become muddled as he moved from one color to the next. In places where the elements do happen to butt up against one another, Lucien avoided over-blending the colors by working with a loaded brush (see fig. 21, e.g., where the paint of the sky has been applied while the hilltop was still wet. For the most part, areas of color have not blended together, but on the left side, the pinkish paint has been dragged through the green). This adds to the highly textured paint surface.

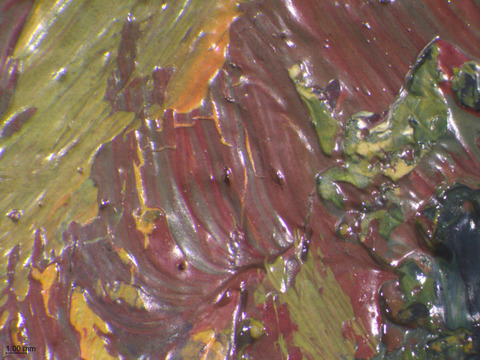

The texture of the paint is fairly thick. It retains brush marks and leaves peaks when the brush is lifted perpendicular to the paint surface (fig 22).

A multitude of different kinds of brushstrokes can be seen in this painting. There are linear strokes like the straight red hatch marks in the tree on the left and blocky square strokes denoting the roofs in the distance (fig. 23). A network of highly worked zig-zagged and hatched marks can be observed in the sky (figs. 24, 25). One can observe different kinds of curved strokes, like short comma-like marks in the trees, as well as long strokes that follow the contours of the hills in the foreground. There are also rounded dots and dabs denoting dappled sunlight on the grass.

After most of the paint layer was dry, Lucien added dabs of lighter colors on top and modified contours (fig. 26). It seems Lucien preferred the appearance of the blue underpainting when it emerged from between compositional elements, and he even added it back in where it had been covered by layers of paint (fig. 27).

For the sky, Lucien depicted the transition from one color to the next as distinct horizontal stripes. This can also be seen in all three of his paintings at the Courtauld Gallery (figs. 28–30).

There is a pink and purple initial underlayer detectable in the bottom half of the sky that was allowed to dry before the web of blue and yellow brushstrokes were added on top (fig. 31). This layer dissipates towards the top half of the sky, where one can simply see the white ground showing beneath the upper layer of brushstrokes (fig. 32).

Painting Tools:

Small and medium sized round brushes (fig. 33).

Binding Media:

Drying oil (untested)

Color Palette:

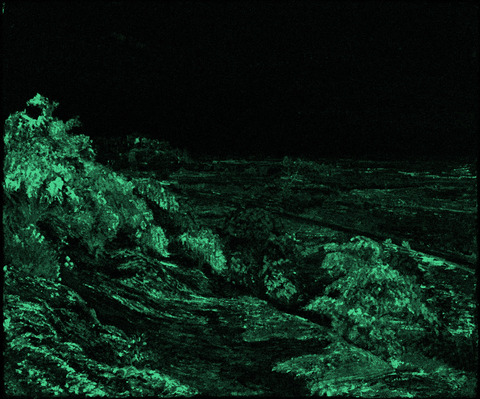

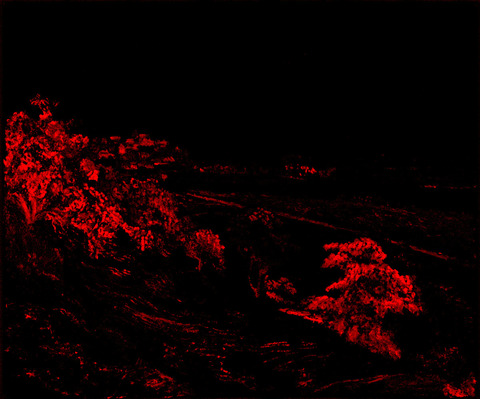

The MA-XRF analysis found copper in the green paint passages, which overlaps exactly with the elemental map for arsenic (fig. 34). The presence of these two elements indicates the use of emerald green paint.

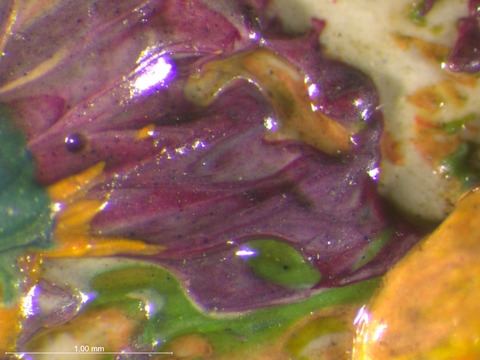

The MA-XRF scan for chromium indicates the use of chrome yellow in the pale-yellow passages on the horizon line in the far distance (fig. 35). It is also present in the mixtures that make up the orange color that represents the warm light of the setting sun dappled on the tops of the leaves and grass. It is also used in various proportions to lighten the green passages and shift them to a warmer hue. Chromium is also present in cooler green passages, which indicates the use of viridian. The range of different greens can be seen clearly in the photomicrograph below (fig. 36).

The blue in the sky is likely French ultramarine. The pigment was found in all paintings by Lucien included in the 2013 study.26 SEM-EDS analysis on Sample a, a cross section from the sky, detected the presence of sodium (Na), aluminum (Al) and silicon (Si) in the blue pigment particles, which is consistent with French ultramarine. Since the presence of this pigment was confirmed in the underdrawing by Raman spectroscopy, it can be assumed that it was already on the artist’s palette.

Vermilion contributes to the salmon pink color dappled within the leaves of the trees in the middle ground and making up the diagonal road and roofs of the houses in the distance. This was inferred from the detection of mercury (Hg) in these passages using scanning MA-XRF (fig. 37). This pink color is distinctive in Lucien’s color palette and is seen in many of his paintings. According to the 2013 study, “[Vermilion] appears consistently in mixtures with white and yellows to produce bright pinks, oranges and purples."27 It can be seen in all three of the Courtauld’s paintings examined in the study: Old Mark’s Field, Coldharbour, Surrey (1915), Le Brusq (1923), and Rade de Bormes (1923).

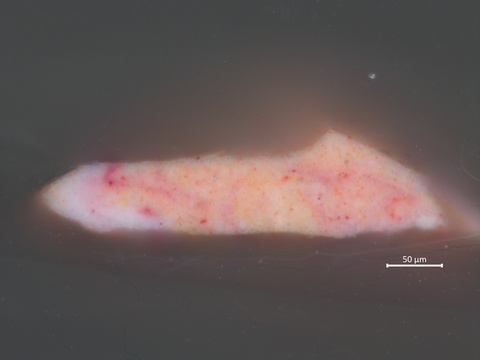

Another red pigment is also present in these areas. The particles are very small and cooler toned red than vermilion (fig. 38). The finely milled red particles can be seen in cross section, swirling through the paint layer. Since the particles are extinguished in ultraviolet irradiation, the red pigment is not likely to be madder lake but may be cochineal or a synthetic organic pigment (figs. 39, 40). This could not be confirmed with analysis.

White was used in paint mixtures throughout the work. The extent of the use of white can be seen in the MA-XRF scan for lead (Pb), which is indicative of lead white (fig. 41). Lead white was added to help unify the bright contrasting colors in a technique known as peinture claire.28

Condition of Paint

The paint layer is in excellent condition. Of the few age cracks visible, the paint appears to be stable. Unlike some other paintings by Lucien (Le Brusq, for example), the paint layer is well bound to the ground. There are also some minor drying cracks in the thickly painted areas (fig. 42).

Description of Varnish/Surface Coating

The painting is unvarnished. Like his father, Lucien “sought an effect of surface mattness and roughness, attained by using semi-absorbent grounds that would ‘wick’ away medium from the paint and promote rapid drying, helping to produce porous, rough paint surfaces which scatter light."29 Multiple paintings by Lucien are known to have a label on the back attached by his wife Esther that reads, “It was Lucien Pissarro’s invariable experience that in any of his pictures he allowed to be varnished, the values were all changed and the picture spoilt—the harm increasing as the varnish darkened. Whereas those pictures left unvarnished retained all their original freshness. The above applies equally to the work of his father, Camille Pissarro."30

Analyzed Observed Documented

| Type of Varnish | Application |

|---|---|

| Natural resin | Spray applied |

| Synthetic resin/other | Brush applied |

| Multiple Layers observed | Undetermined |

| No coating detected |

Condition of Varnish/Surface Coating

The 2022 cleaning resulted in the near total removal of the surface coating. There are still minor remnants of the B-67 varnish on the surface that could not be removed. In the deep interstices of the paint are remnants of a natural resin varnish and some dirt trapped underneath. This can be observed under the microscope.

Description of Frame

Original/first frame

Period frame

Authenticity cannot be determined at the time/ further art historical research necessary

Reproduction frame (fabricated in the style of)

Replica frame (copy of an existing period frame)

Modern frame

Frame Dimensions:

Outside dimensions: 71.8 × 82.6 cm

Rebate dimensions: 54.3 × 65.7 cm

Sight size dimensions: 51.8 × 63.2 cm

Rail width: 9.5 cm

Distinguishing Marks:

Top rail; back left; black plastic strip from mechanical label-maker, white letters in relief:

“55. RYE FROM CODBORO LUCIEN PISSARRO”

Description Of Molding/Profile

The primary frame measures 6.9 cm wide and is constructed from a wood substrate with applied ornament. The profile is a modified Baroque style with Louis design influences. There is a small running bead design along the side edge and a narrow scotia supporting an applied gadrooned bead at the top front outer edge. The front cove is unworked with a narrow taenia at the base. The sight edge has an applied band of leaf and bud ornament on a hatched background with a cavetto edge. At the outer corners, there is a pierced demi-shell motif with trailing flower and stem ornament. The surface finish comprises a layer of acrylic gesso, resin molded applied ornament, a red pigmented ground, and what appears to be metal leaf. Imitation flyspecks, painted flaws, and abrasions have been applied to antique the tone of the finish.

The secondary linen-covered flat slip frame with a slant sight edge measures 3.5 cm and is secured into the rabbet of the primary frame with finishing nails.

Both the primary and slip frames have 45-degree miter joinery and are secured at the corners with nails.

Condition of Frame

The primary frame is structurally secure and is in good condition cosmetically. The secondary slip frame has a cracked rail on the back where part of the back edge has a splintered loss on the right-side rail that slightly decreases the rabbet depth (fig. 46)

Notes

-

Lucien founded the Eragny Press in 1894. In addition to being a painter, Lucien was a prolific printmaker, producing his books under his own press and making illustrations for other publications. The press was named after the area of France that his family moved to in the beginning of the 1880s, where Lucien’s painting career had begun. See C. Harrison, J. Whiteley, and S. Shorvon, Lucien Pissarro in England: The Eragny Press 1895-1914 (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2011), 39. ↩︎

-

Anne Thorold, A Catalogue of the Oil Paintings of Lucien Pissarro (London: Athelney Books, 1983), 4. ↩︎

-

W.S. Meadmore, Lucien Pissarro (London: Constable and Company, 1962), 95. ↩︎

-

W.S. Meadmore, Lucien Pissarro (London: Constable and Company, 1962), 138–140. ↩︎

-

Anne Thorold, A Catalogue of the Oil Paintings of Lucien Pissarro (London: Athelney Books, 1983), 99. ↩︎

-

Anne Thorold, A Catalogue of the Oil Paintings of Lucien Pissarro (London: Athelney Books, 1983), 17. ↩︎

-

“MEK” is methyl ethyl ketone. ↩︎

-

Martin J. Radecki, Examination Report, undated (1981?), p. 1–2, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Martin J. Radecki, Examination Report, undated (1981?), p. 2, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

According to the treatment report, the mixture contained “Ivory Flakes 12gr, benzine 50 ml, and deionized water 50 ml”. See Martin J. Radecki, Examination Report, undated (1981?), p. 1-2, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

“PVA AYAB” is a proprietary low-molecular weight polyvinyl acetate resin that was discontinued by manufacturer Union Carbide in the 1980s. ↩︎

-

Martin J. Radecki, Examination Report, undated (1981?), Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

David Miller, IMA Conservation Department Work Request Form, 1 July 1999, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Polyisobutyl methacrylate or PiBMA ↩︎

-

A specific version of the B-67 varnish, Lucite® 2045, is known to crosslink on exposure to heat and UV light in normal gallery conditions. It may become very difficult to remove, requiring increasingly polar solvents. See R.L. Feller, N. Stolow, and E.H. Jones, On Picture Varnishes and Their Solvents (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1985). ↩︎

-

Alex Chipkin, Conservation Examination Report & Treatment Proposal, 14 December 2021, p. 7, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

For all areas tested, the specular reflection was excluded. Testing was conducted by Dr. Jennifer Shankwitz using a Konica Minolta Spectrophotometer CM-700d. ↩︎

-

Don Johnson, “Thread Count Report, Rye from Cadborough, Lucien Pissarro, 1913 (T167/79.284) from the Indianapolis Museum of Art,” December 2021, p. 1, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

According to an 1888 table of ready-stretched canvases from Bourgeois âinè. See D. Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: National Gallery in association with Yale University Press, 1991), 46. ↩︎

-

See ground composition of Old Mark’s Field, Coldharbour 1916 in Lydia Gutierrez and Aviva Burnstock, “Technical Examination of Works by Camille and Lucien Pissarro from the Courtauld Gallery,” ArtMatters 5 (2013): 13, https://www.amjournal.org/_files/ugd/14a82d_1cd5fda55c9d4cdbb5cf6168377f1fd2.pdf. Old Mark’s Field, Coldharbour was also supplied by H. J. Pursey of Hammersmith, London. The elements were identified using EDX at The Courtauld and DTMS at the Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage (ICN). ↩︎

-

See A. Callen, ‘“The Unvarnished Truth: Mattness, ‘Primitivism’ and Modernity in French Painting, c. 1870–1907,” The Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 741. ↩︎

-

A.F. Grace, A Course of Lessons in Landscape Painting in Oils (London: Cassell, Petter, Galpin, 1881), 85–88, quoted in M. Stols-Witlox, A Perfect Ground: Preparatory Layers for Oil Paintings 1550–1900 (London: Archetype Publications, 2017), 147. ↩︎

-

Lydia Gutierrez and Aviva Burnstock, “Technical Examination of Works by Camille and Lucien Pissarro from the Courtauld Gallery,” ArtMatters 5 (2013): 17 https://www.amjournal.org/_files/ugd/14a82d_1cd5fda55c9d4cdbb5cf6168377f1fd2.pdf. ↩︎

-

For discussion of French ultramarine in other paintings by Lucien, see Lydia Gutierrez and Aviva Burnstock, “Technical Examination of Works by Camille and Lucien Pissarro from the Courtauld Gallery,” ArtMatters 5 (2013): 17, https://www.amjournal.org/_files/ugd/14a82d_1cd5fda55c9d4cdbb5cf6168377f1fd2.pdf. ↩︎

-

See D. Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: National Gallery in association with Yale University Press, 1991), 160–162. ↩︎

-

Lydia Gutierrez and Aviva Burnstock, “Technical Examination of Works by Camille and Lucien Pissarro from the Courtauld Gallery,” ArtMatters 5 (2013): 14, https://www.amjournal.org/_files/ugd/14a82d_1cd5fda55c9d4cdbb5cf6168377f1fd2.pdf. ↩︎

-

Lydia Gutierrez and Aviva Burnstock, “Technical Examination of Works by Camille and Lucien Pissarro from the Courtauld Gallery,” ArtMatters 5 (2013): 18, https://www.amjournal.org/_files/ugd/14a82d_1cd5fda55c9d4cdbb5cf6168377f1fd2.pdf. ↩︎

-

See discussion of peinture claire in Camille’s Le Côte des Beufs, L’Hermitage in D. Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: National Gallery in association with Yale University Press, 1991), 90. ↩︎

-

Lydia Gutierrez and Aviva Burnstock, “Technical Examination of Works by Camille and Lucien Pissarro from the Courtauld Gallery,” ArtMatters 5 (2013): 16, https://www.amjournal.org/_files/ugd/14a82d_1cd5fda55c9d4cdbb5cf6168377f1fd2.pdf. ↩︎

-

Paper label seen on at least three of Lucien’s paintings in the Ashmolean stores (seen first-hand by Alex Chipkin). This quote was transcribed from a photograph of the back of Village d’Eragny (1885) by Camille Pissarro reproduced in Anthea Callen, “The Unvarnished Truth: Mattness, ‘Primitivism’ and Modernity in French Painting, c. 1870–1907,” The Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 740. Esther worked very closely with her husband and knew his working methods well. She managed her family’s affairs when Lucien was alive and donated the private family collection to the Ashmolean soon after his death, which is presumably when the labels were attached. ↩︎

Additional Images