OVERVIEW

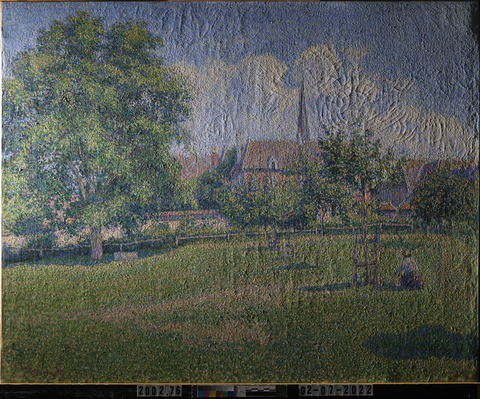

Identification number: 2002.76

Artist: Camille Pissarro

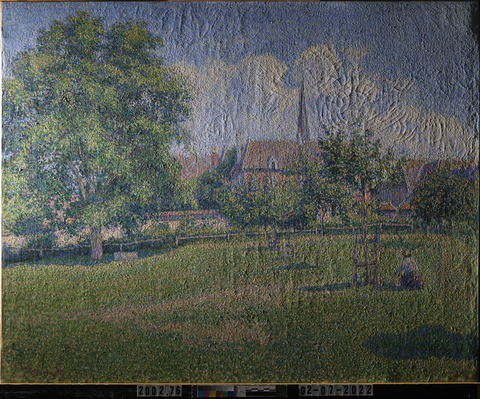

Title: The House of the Deaf Woman and the Belfry at Eragny

Materials: Oil on canvas

Date of creation: 1886

Dimensions: 65.1 × 81 cm

Conservator/examiner: Alex Chipkin with contributions from Laura Mosteller and Dr. Gregory D. Smith

Examination completed: 2022

Distinguishing Marks

Front:

The artist’s signature and the date, “C. Pissarro. 1886” can be seen on the bottom left-hand side of the painting written in red paint. The signature was painted after the underlying paint layers were fully dry (fig. 1).

Back:

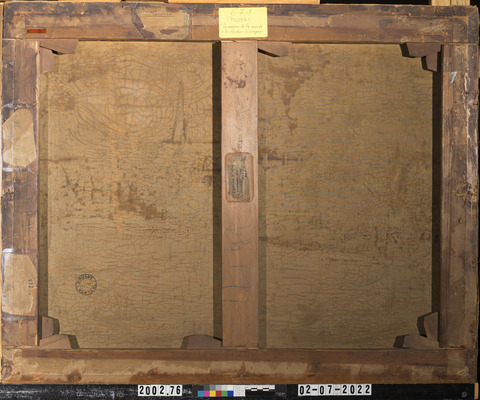

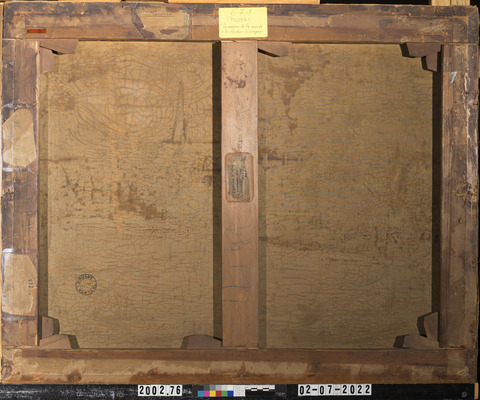

There are various paper labels and inscriptions on the stretcher bars. There are two labels on the left vertical stretcher bar, one of which reads “Durand Ruel” written in blue (zoom into fig. 2 to see the inscriptions). There is also a stamp from the import/export office in Paris called Douane Centrale, in the bottom-left quadrant of the canvas.

Historical Context

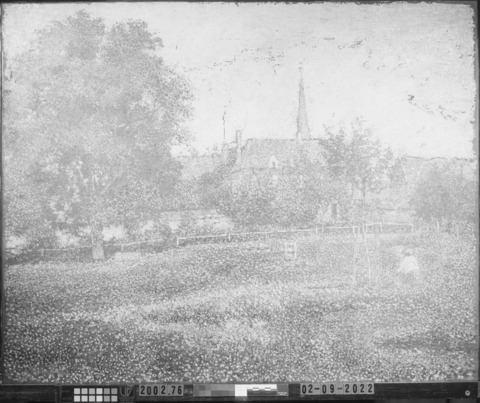

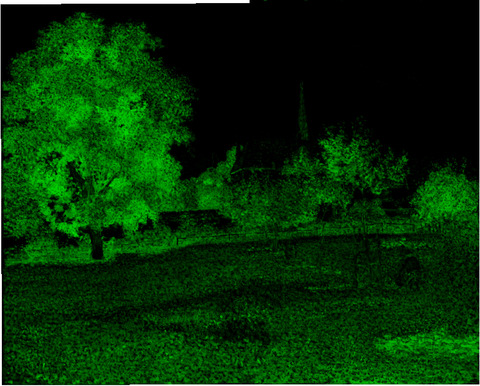

In 1884, Camille and his family moved to Éragny, where he painted many landscapes in the area. This scene is painted looking north, towards his neighbor’s house and the steeple of the Éragny church (fig. 3). Another painting, View from My Window, was started during the same year and is painted looking west from the second-floor studio located in his house (fig. 4).1

On the left-hand side of the painting, a large walnut tree dense with bright green foliage dominates the scene. The wall that surrounds the garden divides the landscape in half between the grassy lawn of the foreground and the sky. A woman with a basket is crouched by a thin tree supported with stakes on the right-hand side, gardening in the sun. Evenly spaced shadows begin from the right-hand corner of the painting and continue to the center, giving the work a sense of depth as they recede into the distance. The shadows lead the eye to the brick house and steeple behind, which pierces though the structured clouds.

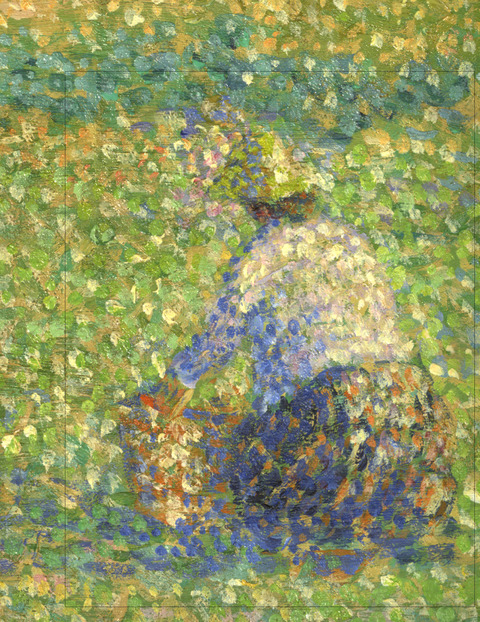

The work was painted during a brief five-year period in which Camille was experimenting with pointillism. Before sending this painting to an exhibition in Brussels, Pissarro wrote of his painting technique, “I'll take with me the two canvases I painted for Brussels; I put a lot of work into the one for Durand. I toiled on it for fifteen days, I think it's greatly improved, more luminous; it’s strange that with the Pointillist technique, given time and patience one gradually achieves a stunning softness... If I had had the time, I could have kept working on it a lot more, I'm sure it would have become amazingly refined!"2 The small dots give the painting a glittering appearance when viewed at a distance.

In 1885, Pissarro met Georges Seurat, who, along with Signac, was developing a new technique of pure tone division in which he employed dots of color to record visual sensations. Camille and Seurat started a correspondence, sharing thoughts on color theory, materials, and techniques. Seurat and other Post-Impressionist artists, as well as critics like Félix Fénéon, were influenced by the new scientific theories put forth by French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul and American physicist Ogden Rood. These scientists' theories about light and color vision, such as simultaneous contrast and local versus spectral color, were incorporated by the artists into their painting techniques.3 The Pointillist technique consisted of painting small round dabs of complementary colors adjacent to one another the intended result being that colors would appear more vibrant than those of traditional paintings. Sometimes the adjacency was not intended to be complementary, but to cause color mixing—blending optically—each dab of paint like photon of light.4

Camille adopted Pointillism and advocated for others using this new method. In 1886, he entered Seurat, Signac, and Lucien into the eighth and last Impressionist Exhibition. Seurat debuted his groundbreaking A Sunday on La Grande Jatte. The IMA work was not completed at that time, but he did show The House of the Deaf Woman alongside A Sunday on La Grande Jatte in Brussels with Les Vingt (Les XX) the next year.5 On March 1, 1887, Camille wrote to his son Lucien, “Paulin has gone to Brussels to the ‘Vingt,‘everybody has been there, he told me that…my things showed up very well, and were clear and colorful. It seems that Durand-Ruel was there, too. I think that there is a veering to the new technique, if they dislike the large Seurat at least they admire the small canvases."6 Pissarro exhibited this work again that year in Paris at Galeries Georges Petit.7

Camille’s strict adherence to the Pointillist technique only lasted about five years. By the late 1880s, he had become dissatisfied with the painstaking technique. He wrote to his son Lucien from Paris on the 20th of February 1889, “I am at this moment looking for some substitute for the dot; so far I have not found what I want, the actual execution does not seem to me to be rapid enough and does not follow sensation with enough inevitability…"8 Later in the century, he shifted away from “pointilisme exclusif absolu,"9 but maintained the concept of tonal division. This can be seen in Woman Bathing Her Feet in a Brook (1894) in the IMA’s collection.

Summary of Treatment History

Before arriving at the IMA, the painting was treated by Bernard Depretz in Paris probably just before it was put up for sale. He cleaned the painting with a mixture of isopropanol, iso-octane, and white spirits. He removed the prior varnish (Depretz believed this to be the original varnish) and applied a final coating of Rembrandt Retouch Varnish and Rembrandt Final Varnish.10 In his condition report, IMA Conservator David Miller asserted that it is unlikely that the previous varnish was original, given that, based on the literature, Pissarro did not routinely varnish his paintings, even before he met meeting Seurat and learned Neo-Impressionist theory.11 He described the varnish as glossy and observed that it had “saturated the colors, over emphasizing the dark blues and greens in particular."12 Miller recommended removal of the inappropriate recent glossy varnish and the creation of an historically correct frame. He observed that the painting was in plane but slightly slack and that it “exhibits some minor bowing out, lumps from debris trapped between the bottom stretcher bar and the fabric, and some minor stretcher creases along the vertical center stretcher crossbar. The canvas verso is stained from varnish/cleaning solvents through craquelure in the paint and ground.” Miller pointed out several losses to the ground on the upper right side.13 In a handwritten treatment report, he described the ground as thin, and “tan/pinkish in color” and that it “has been stained and darkened by varnish and dirt.” He concluded that the ground was likely applied by the artist and is absorbent or semi-absorbent and questioned whether it is bound in some proportion of oil, as it is soluble in acetone but not readily in water.14

Under the microscope, Miller observed a “grayish, hazy material” on the dark blue colors and theorized that it could be residue from the prior varnish, or residual surface not cleaned before the painting was revarnished.

In an attached diagram, Miller indicated losses and lifting paint mostly on the right side and perimeter of the canvas, as well as along the contour of the roof lines that “require minor consolidation treatment."15

According to the treatment report, Miller noted that during the cleaning the “dark blues and some greens” were sensitive, and posited this sensitivity was likely a result of the prior cleaning treatment. Therefore, he thinned the varnish as much as possible to make it appear unvarnished. Removing the varnish also removed the gray grime mentioned above. His cleaning “restored vibrancy and proper tonal relationships” and “improved special balance and detail.” After cleaning, he was able to observe that the dark blue passages were thinly painted.

He performed consolidation of the vulnerable areas of paint with sea gel which he left on the surface as an isolation layer before inpainting. He inpainted with Lefranc & Bourgeois with xylene and did not add any final coating to the entire work.

Miller tapped in the stretcher keys to tighten the canvas. He dry-cleaned the back, removing the debris that had been noted above stuck between the stretcher and the canvas, but he couldn’t remove a protrusion on the bottom-right corner.

Miller then covered the paper labels on the stretcher bars with Mylar and constructed a “passive back” with Foamcore and Artcore adhered with Jade 384-403N. The painting was fitted into a custom-made frame from Bark Frameworks NYC.

Current Condition Summary

Overall, the painting is structurally stable. It remains unlined, and the canvas is planar, if slightly slack. There is craquelure throughout the painting as is expected for an unlined painting of this age. The ground and paint layers are well bound.

Methods of Examination and Imaging

| Examination/Imaging | Analysis (no sample required) | Analysis (sample required) |

|---|---|---|

| Unaided eye | Dendrochronology | Microchemical analysis |

| Optical microscopy | Wood identification | Fiber ID |

| Incident light | Microchemical analysis | Cross-section sampling |

| Raking light | Thread count analysis | Dispersed pigment sample |

| Reflected/specular light | X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) |

| Transmitted light | Macro X-ray fluorescence scanning (MA-XRF) | Raman microspectroscopy |

| Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence (UV) | ||

| Infrared reflectography (IRR) | Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) | |

| Infrared transmittography (IRT) | Scanning electron microscope -energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) | |

| Infrared luminescence | Other: | |

| X-radiography |

Technical Examination

Description of Support

The work is painted on a fine, plain-weave canvas with a thread count of 28.3 × 30.4 per cm.16 The painting measures 65.09 cm × 80.96 cm, which corresponds to the standard number 25 portrait size canvas oriented horizontally (81 × 65cm).17 The canvas weave of this painting was found to match to a painting by his son Lucien, Interior of the Studio (1887), which happens to be in the IMA at Newfields’ collection.18 This suggests that both paintings’ supports were cut from the same bolt of fabric.

Auxiliary Support:

Original Not original Not able to discern None

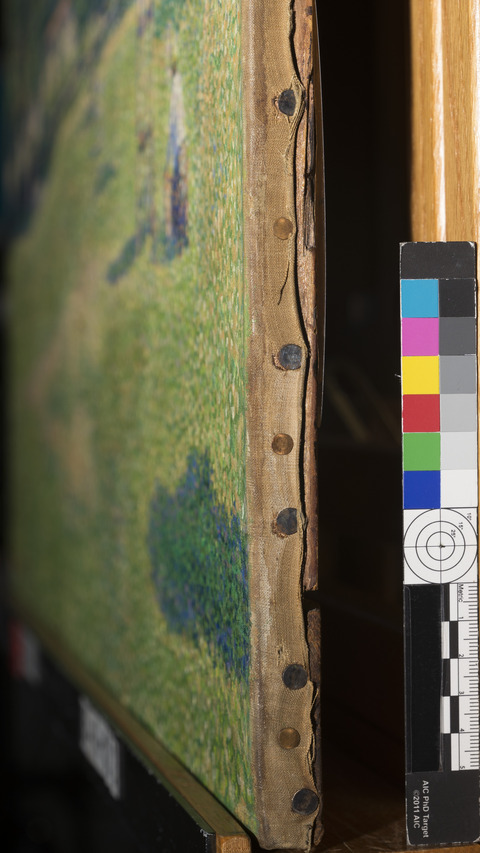

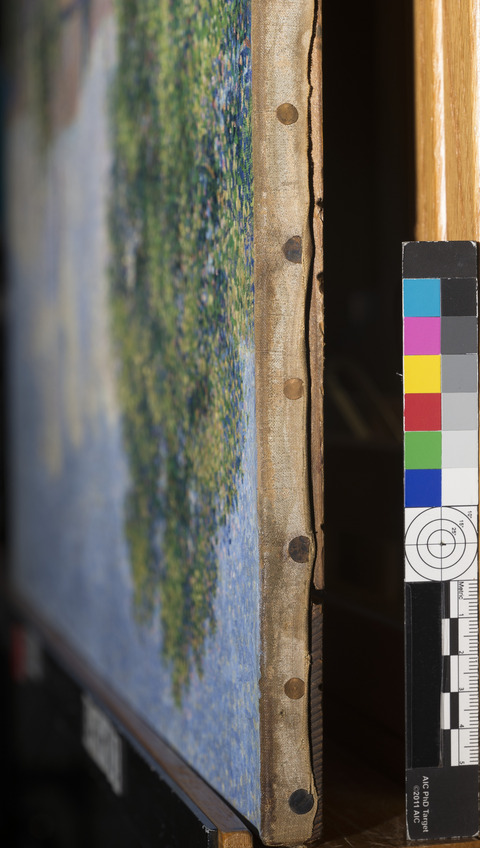

The canvas is mounted onto a five-member stretcher with mortise and tenon joints at the corners and a center vertical member (fig. 2). In his 2001 condition assessment, conservator David Miller writes, “The painting appears never to have been removed from its original five-member keyed stretcher, but additional new copper tacks were added between the original tacks during the restoration for extra support."19 Cusping associated with the original tacks is visible on the tacking margins, which supports the assertation that the canvas has never been removed from the stretcher (fig. 5).

Attachment to Auxiliary Support:

There are 97 tacks affixing the painting to the stretcher.

Condition of Support

The canvas is a little slack but holding in plane. On the back, stains are visible, most probably a result of the cleaning process, which caused the varnish to penetrate

through the craquelure and exposed ground between painted forms. This has caused a stain in the shape of the contour of the steeple (fig. 2). This staining was also mentioned in Miller’s condition report (see Summary of Treatment History above). All 10 stretcher keys are present but are not secured to the stretcher. There are remnants of partially removed paper tape on all four stretcher bars.

Description of Ground

Color:

Translucent dark beige

Application:

The thin layer of ground has filled in the weave of the canvas. Under magnification, it appears that the peaks of the canvas are bare, indicating that the ground may have been abraded to create a smooth painting surface (fig. 6). This was also noted in Miller’s conservation report: “The canvas appears to have been very thinly primed with a translucent (absorbent?) pinkish-tan colored material…where the ground is visible through the brush strokes it occasionally has an abraded appearance—dots are missing along the tops of the threads—this may be part of the original knife scraping application and not damage."20 This technique has also been observed in non-Pointillist works by Camille in other collections.21 The white ground appears to extend over the tacking margins, which indicates that it has been commercially primed. Because the layer is very thin and has been abraded by age and the curling of the canvas (see Condition of Ground section below), it is difficult to say for certain whether it extends to the edge of the canvas.

Character and Appearance (Does texture of support remain detectable/prominent?):

The surface of the canvas appears smooth through the paint layers.

Thickness:

Very thin

Materials/Binding Medium:

The ground is composed of calcium in gelatin.22 This composition is known for its absorbent properties that, in taking up medium from the oil paint layers, would have contributed to the matte surface effect desired by Pissarro.23 It would also have allowed the paint to dry more quickly between layers, ensuring the separate dabs of paint remained distinct.

Sizing:

Likely gelatin (untested)

Condition of Ground

The ground is in relatively stable condition. There are some small areas of lifting paint on the right-hand side in the sky and the foreground close to the edge. This may be due to the sensitivity of the chalk and glue ground to changes in relative humidity. On the tacking margins, tide lines are visible, possibly caused by the absorption of oil from the paint as well as the previous varnish that had disturbed the ground. Canvas edges are curled up and flexible, possibly having been affected by changes in relative humidity as well as handling. This makes it difficult to discern whether the ground on the extreme edges of the canvas is very thin or nonexistent (figs. 7, 8).

Description of Composition Planning

Methods of Analysis:

Surface observation (unaided or with magnification)

Infrared reflectography (IRR)

X-radiography

Analysis Parameters:

| X-Ray equipment | GE Inspection Technologies Type: ERESCO 200MFR 3.1, Tube S/N: MIR 201E 58-2812, EN 12543: 1.0mm, Filter: 0.8mm Be + 2mm Al |

|---|---|

| KV: | 24 |

| mA: | 3.0 |

| Exposure time (s) | 90 |

| Distance from x-ray tube: | 36 |

| IRR equipment and wavelength | Modified Nikon D610 camera with a Coastal Optics lens and X-nite 1000C filter |

Medium/Technique:

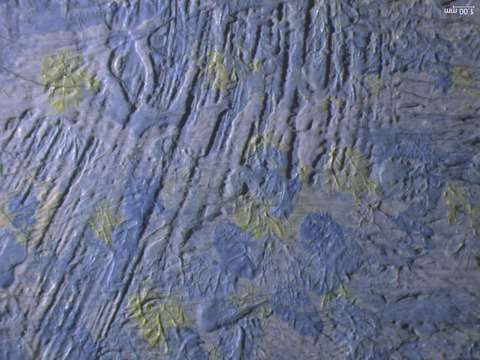

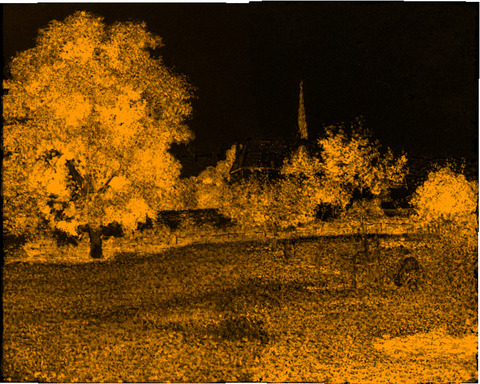

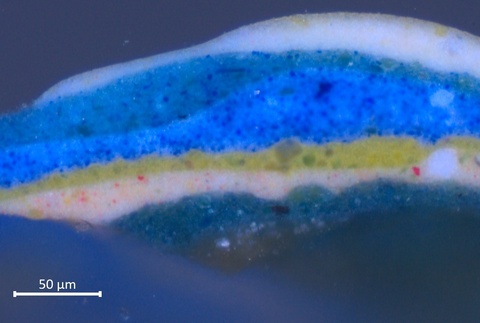

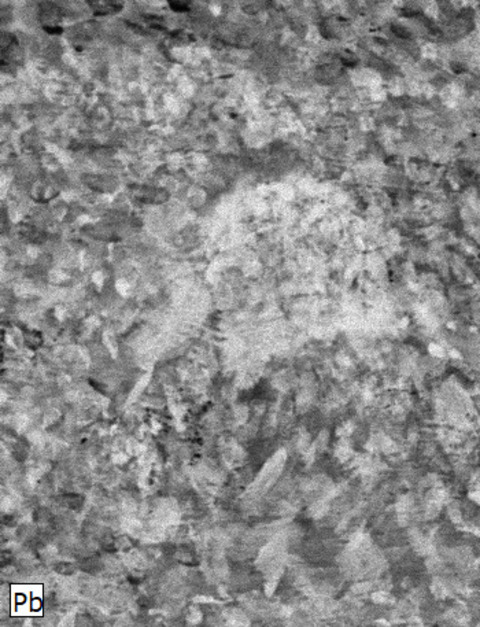

Although at first glance it appears as if this landscape is made up completely of small dots, Camille began this work in much the same way as his non-Pointillist works. He applied thin swaths of color underneath the complex veil of dots: he blocked out main elements of the landscape in discrete areas with a narrow space of ground left exposed around the contours that can be observed under the microscope (see photomicrograph, fig. 9). This can also be seen in the X-radiograph and MA-XRF scan for calcium (fig. 10) where the calcium-containing ground is detected. A similar technique was used by Seurat and is demonstrated in both Bathers at Asnières (1884) and the A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884), where the larger compositional elements of the landscape such as the riverbank, water, and sky were laid in with a broad, thin layer of lean paint.24

Features of this initial paint layer can be seen in the X-radiography of House of the Deaf Woman (fig. 11). The sky on the upper-right quadrant displays swirling and open zig-zag brushstrokes. In the foreground, Camille laid in sweeping horizontal brushstrokes. Spaces between the forms can be observed. No carbon-based underdrawing was detected in the infrared image. However, under magnification, there is a blue outlining for the figure in the foreground painted over the initial blocking-in layers of paint. In the photomicrograph below (fig. 12), we can see that the blue paint stroke that outlines the woman’s back is painted over the already dry green underlayer. This indicates that the figure was added later. The colorful dots are then laid in on top, staying within the confines of those lines.

Description of Paint

Analyzed Observed

Application and Technique:

Over the initial underlayer, Camille built up layers of dots, allowing each layer to dry to avoid the mixing of paint on the surface of the canvas. In general, for each layer of dots Camille used progressively smaller and rounder strokes. The size of the brushstrokes as well as his wet-over-dry technique can be seen clearly under magnification (fig. 13).

The stiff base layer paint has retained the marks of the bristles and the next layer skips along the furrows. The topmost layer of dots sits on top of the textured underlayers, retaining the peaked shape produced by the round brush as it lifted off the canvas (fig. 14). Depending on what is being depicted, Camille’s brushstrokes diverge in slight ways from this general pattern. For the sky, he uses more broadly spaced dots that barely overlap, showing much of the initial broad underlayer below.

To depict the leaves on the trees, Camille used mostly rounded dots (fig. 15). However, hatched comma-shaped marks can be seen underneath, and without a layer of dots above (fig. 16).

The grass in the foreground is made up of short, separated strokes applied in a herringbone pattern (zoom into the foreground of the raking light image, fig. 23). Once dried, more rounded dots were overlayed (fig. 17).

The wall that separates the garden from the neighbor’s house is made up of horizontal squared strokes, following the pattern and shape of bricks (fig. 18).

Camille depicted the terra-cotta roofs of the houses with the smallest and most closely spaced round dabs of paint (fig. 19).

Linear strokes were used for the thin wood fence just before the wall, as well as the blue steeple (fig. 9; Camille used a vertical yellow sweep of paint to denote the faces of the spire).

Of note is an area in which Pissarro obscured the very top of the steeple just below the orange weathervane with blue paint (fig. 20). This is something he also did in The Banks of the Oise near Pontoise. The orange paint of the rooster blends wet-in-wet with the dark blue paint of the steeple. Camille also obscured the red-orange flue of the middle chimney, adding dabs of blue paint overtop. The red flue can still be seen peeking out from underneath the blue dabs of paint (fig. 21). Interestingly, to the left of this chimney is one which has been left without a layer of dots on top (fig. 22).

As described above, there is some minor mixing of paint on the surface of the painting. Another example is the red chimney flue that overlaps the church steeple, in which the pale-yellow dots have picked up some of the red from the underlying red-orange paint that was still wet (fig. 24).

Painting Tools:

Relative to the dots in subsequent layers, Camille used a large brush for the underlayers, averaging about 16 mm in width. As he built up the layers of dots, he used smaller and smaller round brushes. The dabs also gradually get smaller as objects recede into space. For the next layer of comma-like strokes, he used brushes from 3 to 5 mm wide. For the uppermost layer of round dots, he used brushes as small as 1 mm.

Binding Media:

Oil paint (untested)

Color Palette:

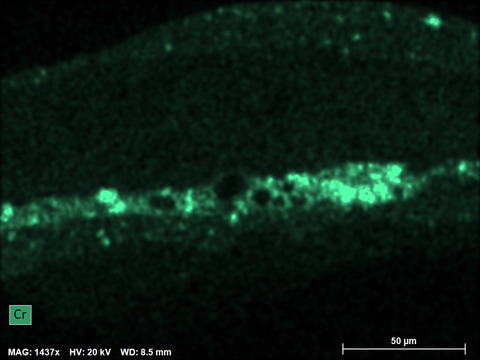

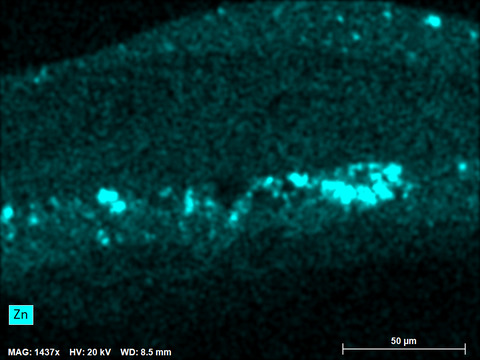

Overlapping MA-XRF maps for copper and arsenic indicate the majority of the green paint used for the foliage and grass is emerald green (fig. 25).

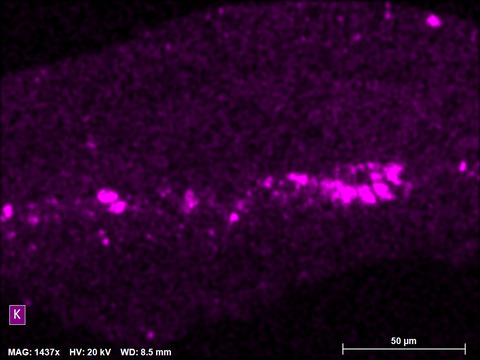

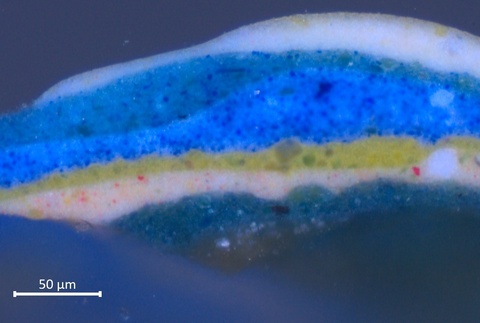

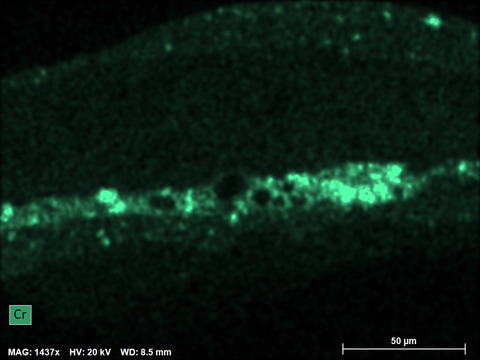

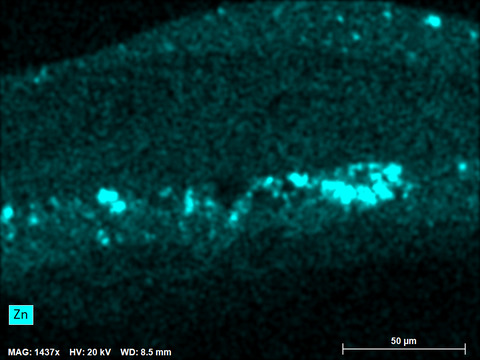

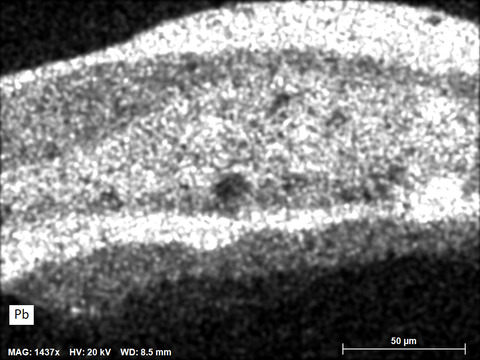

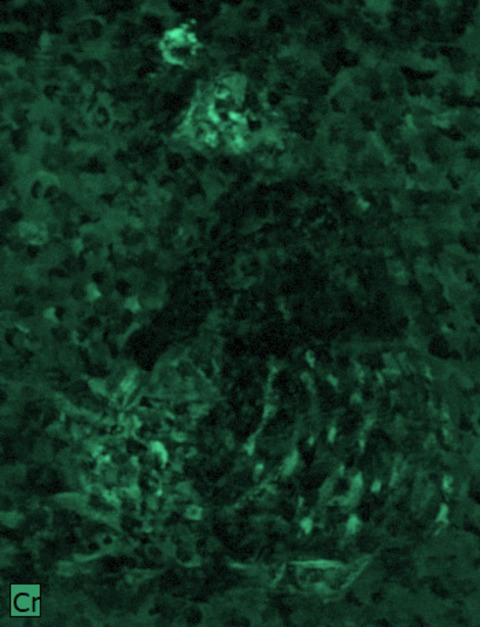

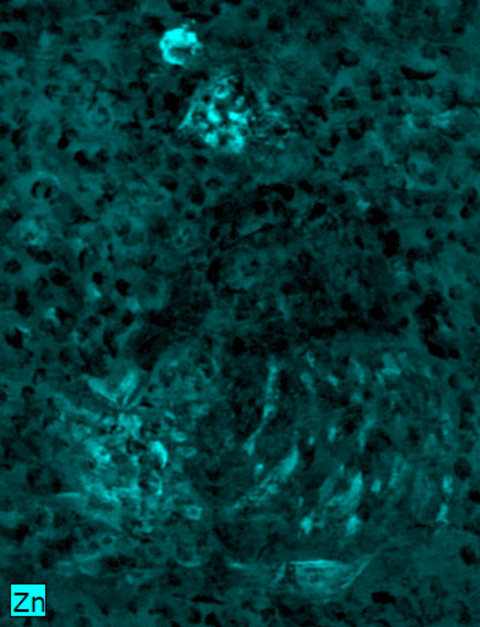

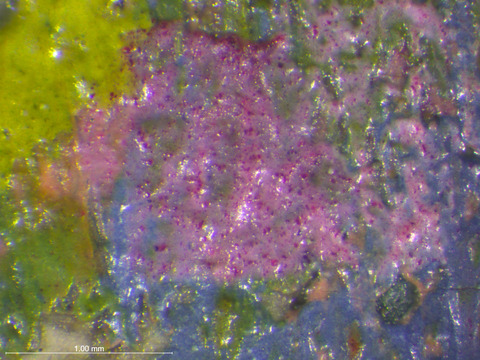

For the yellow paint that appears mostly in mixtures, Camille used a zinc yellow, as indicated by MA-XRF scans for zinc and chromium, which overlap precisely (fig. 26). SEM-EDS analysis of a cross section taken from a pale yellow dab of paint in the tree on the left-hand side detected zinc, chromium, and potassium in the topmost layer and in a lower yellow layer (figs. 27–30).25 As can be seen in the SEM-EDS results, the topmost pale yellow layer contains mostly lead white and a few disparate particles of zinc yellow (fig. 31-34). The pale yellow is also seen in the woman’s back in the foreground, made up of a high proportion of lead white and zinc yellow. Although in the detail MA-XRF scans of the woman, zinc and chromium appear not to be present in the area of these pale dots; this is most probably due to the fact that the higher atomic number lead has blocked the signal of these lighter elements (see detail MA-XRF scans for chromium and zinc, fig. 32-35).

Two blues are used for areas of shadow on the underside of foliage, on the grass under the tree, and the shadow on the lower right-hand side, as well as the steeple in the distance. According to the MA-XRF map for cobalt, a cobalt blue is used in these areas, mixed with a small proportion of white (fig. 36). It is also present in the sky, noticeable mainly in the dots on top of the broadly painted base layer. According to SEM-EDS analysis of a sample taken from the sky, the base layer contains a large proportion of lead white mixed with cobalt blue.

The other blue used is likely French ultramarine. It is darker and has not been mixed with white. As mentioned above in Description of Composition Planning: Medium/Technique section the figure in the foreground has a blue underdrawing that is likely French ultramarine. The IMA’s Woman Washing her feet in a Brook by Camille Pissarro also has a French ultramarine underdrawing, identified with the use of Raman microspectroscopy. It has been found in many of his works from other collections as well.26 Hence it is highly likely that this pigment would have been found on his palette.

In this painting, Camille effectively employed the theory of simultaneous contrast with dabs of orange adjacent to blue shadows, seen mainly in the terra-cotta elements but also in the tree on the left-hand side and the grass. The presence of mercury, detected by MA-XRF, indicates that the red pigment used in the orange mixtures is vermilion (fig. 37). Many of the areas of red have been mixed with zinc yellow, to make what was termed “solar orange” by Fénéon. Solar orange was often used to depict “spectral color,” or the color of warm afternoon light.27

White was mixed into most areas of the painting. Lead was detected with MA-XRF scanning, which indicates the addition of lead white for these passages (fig. 38). White was used to make the overall appearance of the palette more blond. Adding white also made the paints more opaque and further contributed to the matte surface effect.28 The addition of zinc yellow to vermilion passages also contributed to the blond appearance.

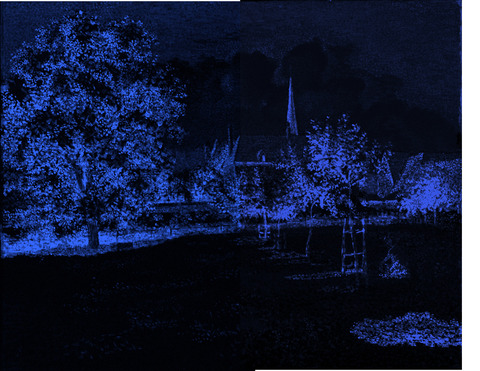

Examination of the painting under ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence suggests the presence of madder lake in many of the orange areas, like the stakes for the trees, the roofs, and the trunk and foliage of the walnut tree (see fig. 41 below). These transparent ruby-like particles are visible under magnification (fig. 39).

Condition of Paint

There are some small losses and lifting paint concentrated mainly on the right-hand side of the painting near the edge (fig. 40). To the right of the steeple are circular impact cracks, which can be clearly seen in raking light (see fig. 23 above). Also observable in raking light is a slight impression of the vertical stretcher bar to the left of the steeple. This is probably due to the slightly slack canvas having bumped against the vertical stretcher member, causing stress on the paint layer that led to paint loss. Under ultraviolet irradiation, retouching can be seen in this area. There is also retouching along the contours of the roofline, clouds, and right-hand edge of the painting.

Description of Varnish/Surface Coating

Analyzed Observed Documented

| Type of Varnish | Application |

|---|---|

| Natural resin | Spray applied |

| Synthetic resin/other | Brush applied |

| Multiple Layers observed | Undetermined |

| No coating detected |

Condition of Varnish/Surface Coating

As stated in the Summary of Treatment History section above, there is little to no surface coating on the painting. The painting appears appropriately matte, which was the preference of Pissarro and other Post-Impressionists at the time.29 View from my Window (mentioned previously in Historical Context) was painted at the same time as this work and has a label attached to the center vertical stretcher bar cautioning others against varnishing the work. The label was written by Esther L. Pissarro, wife of Lucien Pissarro, and it reads, “It was Lucien Pissarro’s invariable experience that in any of his pictures he allowed to be varnished, the values were all changed and the picture spoilt—the harm increasing as the varnish darkened. Whereas those pictures left unvarnished retained all their original freshness. The above applies equally to the work of his father, Camille Pissarro.” 30 Pissarro himself even displayed his works behind glazing as an alternative to varnishing.31

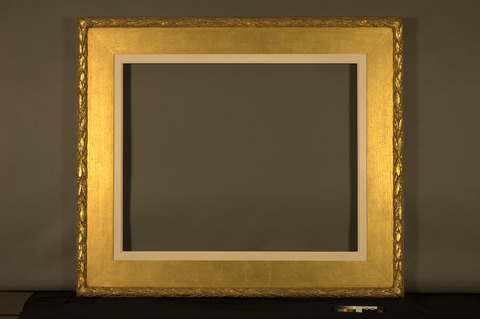

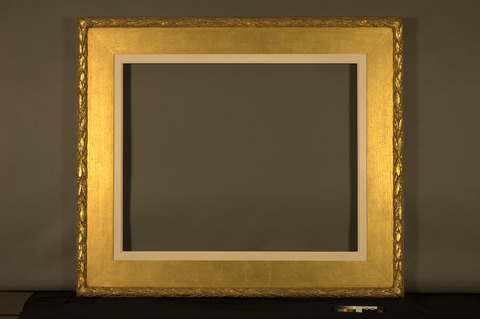

Description of Frame

Original/first frame

Period frame

Authenticity cannot be determined at the time/ further art historical research necessary

Reproduction frame (fabricated in the style of)

Replica frame (copy of an existing period frame)

Modern frame

Frame Dimensions:

Outside dimensions: 94.6 × 110.5 cm

Rebate dimensions: 66 × 81.9 cm

Sight size dimensions: 63.8 × 79.7 cm

Rail width: 14.3 cm

Distinguishing Marks:

White paper label on the back of the frame, bottom rail, left corner; printed in gray ink: “BARK FRAMEWORKS, INC./ 21-24 44th Avenue, Long Island City, NY 11101”

(fig. 41). There are no other marks on the back of the frame—this frame predates the Bark Frameworks practice of using a five-digit number stamped on the back to designate the frame profile.

Description Of Molding/Profile:

The frame profile is a frieze with an applied laurel and berry torus at the outer edge. An unworked slip frame has a flat profile with a cavetto sight edge. The frame was commissioned by the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2002 and made to specifications based on extensive research carried out by the IMA conservators and curators that replicates a design Camille Pissarro described in a letter to his son, Lucien.29

The primary frame construction consists of a 10.6 × 4.3 cm basswood substrate with a 0.64 cm oak veneer on the front and side of the molding. The decorative laurel and berry ornament is applied composition, measuring 3.0 cm wide. The oak frieze is gilded with gold leaf with no ground layer, then rubbed lightly to enhance the wood grain and reveal the lay lines of the leaf. The gilded composition ornament has a gesso and red bole ground. The slip frame is 3.0 cm wide basswood and has a white painted finish (fig. 42).

The gilded portions of the frame have been sealed with a shellac-based varnish that is soluble in alcohol. Both the primary and slip frames have 45-degree miter joinery.

Condition of Frame

The frame is structurally secure, and the gilded finish is in excellent condition. It arrived from the frame maker in 2002 with a damaged lower-right corner join on the primary frame, and the miter join had failed. The corner join was glued with Jade #834-403N, remnants of which can be seen on the back. The damage also resulted in the gilded corner strap composition ornament being cracked, which was consolidated with the Jade adhesive.

________________

29 Excerpt from letter written by Camille Pissarro to his son Lucien, Paris, 15 March 1887: “I believe that my last landscape will be quite good, I shall frame it thus: a one and a quarter inch white margin around the painting, a flat oak surface of three and one half inches and a gilt laurel border of one and one quarter inches: this will look proper, I think, and I may do the same for the other canvases; I have to show my works to best advantage, for you know how the other artists present theirs. So framed, my painting will lose nothing, I hope, and the frame, while severe, will not be too ill-matched with the others nearby.” Cited from John Rewald, ed., Camille Pissarro: Letters to His Son, Lucien (New York: Pantheon, 1943), 102, https://archive.org/stream/lettersto00piss/lettersto00piss_djvu.txt.

Notes

-

View from My Window was started in 1886 and completed in 1888. There are two signatures and dates, the later overwriting the original. Observed by the author at the Ashmolean Museum and noted in Ellen W. Lee, “A Rediscovered Camille Pissarro Acquired by the Indianapolis Museum of Art,” The Burlington Magazine 145, no. 1205 (August 2003): 581. According to the catalogue entry for this painting, the tall barn on the left was later converted into a studio in 1892. It also measures the same as the IMA work. See J. Pissarro and C. Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings (Milan: Skira; Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 2005), 541. ↩︎

-

Quoted in J. Pissarro and C. Durand-Ruel Snollaerts, Pissarro: Critical Catalogue of Paintings (Milan: Skira; Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 2005), 544. The authors also note that Pissarro could be referring also to number 827 in the catalogue. ↩︎

-

John Gage, “The Technique of Seurat: A Reappraisal,” The Art Bulletin 69, no. 3 (September 1987): 449–450, https://doi.org/10.2307/3051065. ↩︎

-

See D. Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: National Gallery in association with Yale University Press, 1991), 83–90; Alan Lee, “Seurat and Science,” Art History 10, no. 2 (June 1987), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.1987.tb00250.x; and Anthea Callen, Techniques of the Impressionists (London: Chartwell Books, 1993), 138–141. ↩︎

-

Les Vingt (The Twenty) were a group of Belgian painters interested in Symbolism who started exhibiting together in the early 1880s. They exhibited artists from other countries and were proponents of Neo-Impressionist painting. The exhibition occurred from February to March, 1887, and the painting appears in the catalogue as no.1, titled Le Noyer, or The Walnut Tree. See Octave Maus, Catalogue de la IVe exposition anuelle des XX (Brussels: Veuve Monnom, 1887), 114. ↩︎

-

See John Rewald, ed., Camille Pissarro: Letters to His Son, Lucien (New York: Pantheon, 1943), 102. In a footnote, the editor mentions that the “large Seurat” referred to by Pissarro is A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of la Grande Jatte. ↩︎

-

Listed as no. 103 in the catalogue. See Galerie Georges Petit, Exposition Internationale de peinture et de sculpture, 6ème anneé, du 8 mai au 8 juin 1887 (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, 1887). ↩︎

-

John Rewald, ed., Camille Pissarro: Letters to His Son, Lucien (New York: Pantheon, 1943), 135. ↩︎

-

Lionello Venturi referred to this painting as an example of Pissarro’s strict pointillist technique, which he called “pointilisme exclusif absolu.” Ludovic-Rodo Pissarro and Lionello Venturi, Camille Pisssarro: Son Art – Son Oeuvre (Paris: Paul Rosenberg, 1939),56, cited in Ellen W. Lee, “A Rediscovered Camille Pissarro Acquired by the Indianapolis Museum of Art,” The Burlington Magazine 145, no. 1205 (August 2003):581. ↩︎

-

In his condition report, conservator David Miller had translated Depretz’s brief treatment report and made a note that the Rembrandt Retouch Varnish and Rembrandt Final Varnish were possibly composed of Ketone Resin N (polycyclohexanone), which was produced between 1967 and 1982. David Miller, “Examination for Purchase Consideration,” September 2001, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

David Miller, “Examination for Purchase Consideration,” September 2001, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

David Miller, “Examination for Purchase Consideration,” September 2001, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

David Miller, “Examination for Purchase Consideration,” September 2001, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

David Miller, treatment report for 2002.76, 2002, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

David Miller, “Examination for Purchase Consideration,” September 2001, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Don H. Johnson, “Thread Count Report La Maison de la Sourde et le Clocher d’Eragny Camille Pissarro 1886 (PS827/2002.76) from the Indianapolis Museum of Art,” May 2022, p. 1, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Inferred from an 1888 table of ready-stretched canvases from Bourgeois âinè. See D. Bomford et al., Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: National Gallery in association with Yale University Press, 1991), 46. ↩︎

-

Don H. Johnson, "Canvas Match Report: Camille Pissarro, Lucien Pissarro PS827, T19 from the Indianapolis Museum of Art," April 2022, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

David Miller, “Examination for Purchase Consideration,” September 2001, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

David Miller, “Examination for Purchase Consideration,” September 2001, Conservation Department Files, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields. ↩︎

-

Lydia Gutierrez and Aviva Burnstock, “Technical Examination of Works by Camille and Lucien Pissarro from the Courtauld Gallery,” ArtMatters 5 (2013): 16. ↩︎

-

Gelatin detected with FTIR analysis. Samples treated with hydrofluoric acid vapor shifting calcium compound IR bands out of the spectral range, leaving only the medium. Calcium carbonate detected with SEM/EDX as well as FTIR. ↩︎

-

Lydia Gutierrez and Aviva Burnstock, “Technical Examination of Works by Camille and Lucien Pissarro from the Courtauld Gallery,” ArtMatters 5 (2013): 16–17. ↩︎

-

See Jo Kirby, Kate Stonor, Ashok Roy, Aviva Burnstock, Rachel Grout, Raymond White, “Seurat's Painting Practice: Theory, Development and Technology,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 24 (2003): 20–21, http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/technical-bulletin/kirby_stonor_roy_burnstock_grout_white2003. ↩︎

-

The pigment is made by reacting zinc oxide with potassium dichromate. See Hermann Kühn and Mary Curran, "Chrome Yellow and Other Chromate Pigments" in Artists Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, ed. Robert Feller (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 1:187–200 ↩︎

-

Lydia Gutierrez and Aviva Burnstock, “Technical Examination of Works by Camille and Lucien Pissarro from the Courtauld Gallery,” ArtMatters 5 (2013): 17–19. ↩︎

-

John Gage, “The Technique of Seurat: A Reappraisal,” The Art Bulletin 69, no. 3 (September 1987): 449. ↩︎

-

Anthea Callen, “The Unvarnished Truth: Mattness, ‘Primitivism’ and Modernity in French Painting, c. 1870–1907,” The Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 746. ↩︎

-

Anthea Callen, “The Unvarnished Truth: Mattness, ‘Primitivism’ and Modernity in French Painting, c. 1870– 1907,” The Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 738–746. ↩︎

-

Paper label seen on a low-quality photo of the back of View from my Window. The same label is seen attached to many works by Camille Pissarro, and this quote was transcribed from a photograph of the back of Village d’Eragny (1885) by Camille Pissarro reproduced in Anthea Callen, “The Unvarnished Truth: Mattness, ‘Primitivism’ and Modernity in French Painting, c. 1870–1907,” The Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 740. ↩︎

-

Gonzague-Privat, L’Evénement, 5 April 1881, quoted in C. Moffett, ed., The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886 (San Francisco: The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986), 367, cited in Anthea Callen, “The Unvarnished Truth: Mattness, ‘Primitivism’ and Modernity in French Painting, c. 1870–1907,” The Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 740. ↩︎

Additional Images